Essay submitted for Individual Education Practice I (EPG 887) at Macquarie University (November, 1993).

Judy Ranka is a Lecturer in the School of Occupational Therapy, The University of Sydney. At the time of writing this essay she was also a part-time graduate student in an MA (Hon) program in the School of Education at Macquarie University

INTRODUCTION:

Education has been defined as the organised, systematic effort to foster learning, to establish the conditions for learning and to provide the activities through which learning can occur (Smith, 1983, p.37). The success of this process is dependent on how well the learning experiences offered match the needs and capabilities of the learners (Knowles, 1984; Zais, 1976). Effective teaching and learning, therefore, is dependent on educational experiences which are ‘individualised’ to learners (Smith, 1983; Knowles, 1973).

Recent, radical changes in knowledge and understanding in numerous fields of inquiry suggest there is a growing rejection of explanations of the world which view entities as independent of their environment or other entities; of adhering to linear, cause-effect predictions of change and of accepting that there can be one universal explanation of events (Bateson, 1979; von Bertalanffy, 1926/1971; Bronffenbrenner, 1979; Gardner, 1985; Giroux, 1990; Goodall, 1986; Prigogine, 1980; Sameroff, 1982). This represents a widespread paradigm shift which opposes linear, Newtonian and reductionist viewpoints (Doll, 1989). Individuals, collective groups, organisations, organs, cells, mathematical structures and chemical compounds, to name a few, reveal incredible uniqueness and unpredictability.

This paradigm shift also confronts traditional and generally applied curriculum designs and frameworks. Doll (1989) suggests that most practice in this area remains based on linear concepts of predicted change described by Tyler (1949, 1979) in which teaching experiences are structured and sequenced in the form of a syllabus and presentation of material is generally in didactic form. The intent of the curriculum is ‘cummulative’, that is, learners gradually acquire (accumulate) pre-determined and specified knowledge. Doll (1989) proposes an alternative view of education which is aligned with the changing views of knowledge and understanding taking place elsewhere. The intent of this alternative curriculum is ‘transformative’ (Doll, 1989). This view emphasises contingency and ambivilance rather than structure (Carter, 1993), and aims to bring about transformation in learners (Giroux, 1988) rather than accumulation. It considers the interdependence which exists between learner, teacher, curriculum practice and curriculum environment and thrives on unexpected challenge and change. ‘Individualised’ education in a transformative curriculum views learners (single learners or collective groups of learners) as entities which have unique educational needs, and stresses an environment where there is mutual respect and trust between all participants (Kitwood, 1990).

Although a return to holistic paradigms is evident in occupational therapy practice (Kielhofner, 1985; Reed, 1984; Townsend, Brintnell & Staisey, 1990), little reference is made in occupational therapy literature to the application of models of occupational therapy to curriculum structure.

Reilly (1958, 1969) encouraged occupational therapy educators to adopt ‘occupation’ as the focus of professional education. Others have suggested a structure for how this could occur (American Occupational Therapy Association, Inc., 1974), and recommended a theoretical basis for the arrangement of curriculum activities (Rogers, 1983). Most occupational therapy literature, however, is concerned with aspects of curriculum practice. For example, authors have described the application of various teaching and learning principles in occupational therapy educational programs, including: self-directed learning (Hollis, 1991; Ranka, Twible & Pitkeathly, 1991) and problem-based learning (Jacobs & Lyons, 1992). Others discuss issues related to curriculum implementation and change (Jantzen, 1977; Leonardelli & Gratz, 1986; Mularski, Nystrom & Grant, 1989; Neistadt, 1987; Pelland, 1987; Rogers, 1980a,b).

Recently, Schemm, Corcoran, Kolodner and Schaaf (1993) provide an example of curriculum modelling which has occupation as its core and systems theory (von Bertalanffy, 1968) as its theoretical foundation. No reference is made to any model of occupational therapy practice as an organising framework for curriculum decisions as originally proposed by the American Occupational Therapy Association, Inc. (1974). The value of a curriculum model which is based on a model of occupational therapy practice lies in its potential to direct educational practice and research in a manner which is congruent with occupational therapy philosophy.

PURPOSE.

The purpose of this essay is to present an initial conceptalisation of a curriculum model which reflects the paradigm shift described earlier. It is founded on principles which arise out of postmodernism, and incorporates aspects of the framework, principles and operations described in the models and frameworks of occupational performance (American Occupational Therapy Association, Inc., 1974; Chapparo & Ranka, 1992). The curriculum model presented is in the formative stage of model development described by Krefting (1985) and others (Creek, 1990; Mosey, 1986; Reed, 1984). A theoretical base is identified, constructs are named and defined and their interactions are explained relative to a ‘curriculum’. Further work is required to refine the constructs and delineate their implications for educational practice.

POST-MODERN PERSPECTIVES:

Postmodern, it has been suggested, “represents a critical reappraisal of modern modes of thought, religious belief and moral conviction” (Waters, 1985, p.113). This reappraisal is advancing holistic and interactionist themes. Specifically, Waters (1986) suggests there is a deepening suspicion of rigid dichotomies between objective reality and subjective experience, fact and imagination, secular and sacred, public and private. Prigogine and Stengers (1984, p.xxvii) summarise by noting that we are, “developing a new dialogue with nature [wherein] our vision of nature is undergoing a radical change toward the multiple, the temporal and the complex”. Conversely, there is a shift away from the universal, stable and simple as asserted by early scholars and proponents of reductionist modes of thinking.

The foundations of what is referred to as ‘postmodern’ may be partially found in the systems work of von Bertalannfy (1926/1971), the developmental biology work of Piaget (1971) and the philosophy of Whitehead (1929). A synthesis of these ideas with developments in the fields of non-linear mathematics and physical chaos appears in the work of Prigogine (1980) and Prigogine and Stengers (1984), and is added to by their work in the field of non-equilibrium thermodynamics.

Prigogine (cited by Doll, 1989, p.244) received the 1977 Nobel Prize for his work on dissipative, or far-from-equilibrium thermodynamic structures. A far-from-equilibrium structure is one which is in the process of ‘becoming’. These structures are in developmental and emergent states. They are unstable and dissipative and are in formative and often chaotic states of far-from-equilibrium becoming (Prigogine, 1980).Stable structures are inert, mechanical structures which occasionally get out of balance (disequilibrium) and then settle back into a state of equilibrium.

While both types of structures exist in the world, Prigogine (1980) believes that far-from-equilibrium structures are more common. He further suggests that dissipative (far-from-equilibrium) structures are not variations of equilibrium situations. A state of equilibrium is analogous to stagnation. An example which illustrates this point is provided by Prigogine and Stengers (1984, p. 148). They refer to a basin of water with hot and cold running taps. If the taps are turned off, the basin of water will gradually resume a state of equilibrium, or loss of energy. Consequently, stagnation, or death by entropy occurs. If, however, the water is boiled or frozen, reaching the relevant temperature produces a sudden transformation of molecules (steam, ice). The change is a quantum leap. To accomplish this, Prigogine and Stengers (1984) assert that communication among molecules must occur, that is, they must communicate to reorganise. The system, therefore, acts as a whole and self-organises. Prigogine and Sengers (1984) describe this process as order arising out of chaos.

Postmodern views in education generally reflect this notion of order arising out of chaos (Berlin, 1992; Hlynka, 1991; McCracken, 1989). This idea of self-organisation and that of far-from-equilibrium structures described by (Prigogine, 1980; and Prigogine & Stengers, 1984) provide the foundations of the curriculum framework proposed here. Doll (1989) summarises three tenets of post-modern thought which emerge from the work described above and outlines the implications of these for the curriculum. These include ideas about open systems, complex structures and transformative change.

Curriculum as an open system:

Systems may be described as interactive units which may be ‘closed’ or ‘open’. Closed systems are analagous to machines. They have inputs and the machine functions as the vehicle for using the input to produce something which becomes the output. Information about the output is returned to the machine as feedback via a feedback loop. This ‘informs’ the machine about whether it should continue to function or cease operating. The machine continues to function until all the inputs cease or feedback indicates a broken part.

Doll (1989) suggests that the traditional, linear curriculum perspectives widely used are closed systems. They have pre-determined ends in the form of objectives, lesson plans which are congruent with those objectives and assessments which are designed to measure accomplishment of the pre-determined objectives. Closure is the satisfaction of the objectives. Alternatively, open systems continually change. Inputs can arise from a number of different sources and this makes change unpredictable. Open systems view reorganisation as fostering growth and transformation, and therefore seek triggers to re-organise.

A post-modern curriculum structure is one which has this capacity to reorganise. It encourages transformation to happen from within rather than by pre-determined methods. It recognises that people, equipment and the environment are an inherent part of the larger curriculum ‘system’.

Curriculum as a complex structure:

Newtonian and reductionist perspectives view existence in terms of linear trajectories, order, uniformity, harmony and simple paths. Postmodern views recognise that reality is complex and web-like with multiple interacting forces (Prigogine & Stengers, 1984; p. xxvii). Knower and known are interactively entwined and multiple interactions are occurring between elements in most situations. Consequently, predictions about how the system will respond to a given change anywhere in the system are difficult to make. This complexity also enables these dissipative structure to reorganise themselves on a higher plane rather than suffer entropy. Complex structures therefore have a history and an unpredictable and more complex future.

A postmodern curriculum structure is also complex with multiple interacting elements. The boundaries between curriculum areas are, in many instances, artificial as are boundaries between teachers and learners and experts and novices. Predictions about change are hard to make (Doll, 1989).

Curriculum as a vehicle for transformative change:

Transformation means that what once was, is now something else. Incremental change is planned, predictable and leads to stagnation (Doll, 1989). Errors made in an incremental or traditional curriculum structure are viewed as ‘wrong’ and corrected. For example, student errors on assignments are viewed as failed learning and students are made to repeat work. Transformation sees errors as necessary perturbations for growth and quantum leaps to occur. This suggests that student errors may encourage quantum leaps in curriculum tasks presented or teaching/learning strategies used.

A postmodern curriculum structure supports the process of transformation or growth; it does not contain and protect a body of knowledge (Doll, 1989). Teachers and learners are viewed as a major stimuli for transformation. They are both encouraged to combine supportive with challenging behaviour to promote a higher reorganisation of knowledge and curriculum practice.

While it is recognised that postmodern views do not hold all the answers for curriculum design (Doll, 1989; Giroux, 1988; McCracken, 1989), educators are challenged to study contemporary developments elsewhere. Many other fields of inquiry have models which pay attention to disequilibrium, internal structures, pathways of development and transformative reorganisation (Doll, 1989). Educators are advised to examine the best practice occurring outside the field of education and develop curriculum models which are multifaceted matrices. Educators are also challenged by these developments to reconsider what it means to be a ‘teacher’ (Bain, 1991).

INITIAL CONCEPTUALISATIONS OF A POST-MODERN CURRICULUM MODEL

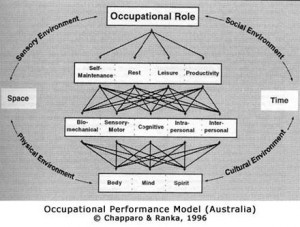

The model of Occupational Performance (Chapparo & Ranka, 1992) presents a framework which organises occupational therapy practice around a common general theme, ‘occupational role performance’. It is a complex and interactive structure which identifies an internal environment (within a person) and an external environment (outside a person). It contains several levels of constructs with multiple interactions occurring at each level and in both environments. It recognises that the system is never passive, activity is always occurring somewhere. Any activity anywhere in the system prompts a response, there is no reductionist hierarchy. The response which occurs is felt throughout the system and may be adaptive or maladaptive. A maladaptive response exists when the system no longer accomplishes its aim; in the case of Occupational Performance, ‘Occupational Role Performance’ has been compromised (Chapparo & Ranka, 1992).

The framework of the Occupational Performance model (Chapparo & Ranka, 1992), as well as the principles and operations of the model provide a vehicle for constructing a model of a ‘postmodern’ curriculum. The remainder of this paper will focus on describing this structure, defining the major constructs and providing examples of their interactions as they relate to a curriculum .

Definition of a Postmodern Curriculum

The major construct around which this model is conceptualised is ‘postmodern’. As described earlier, this term has not been defined. It is a perspective which rejects rigid cause-effect relationships of reductionism, and dichotomies between the objective and subjective, fact and imagined, knower and known (Aronowitz & Giroux, 1991; Doll, 1989; McCracken, 1989; Prigogine & Stengers, 1984; Waters, 1986). It aims for transformation to occur within students; that is, they engage in ‘deep’ learning (Biggs, 1987) and reorganise their knowledge, skills, attitudes and values on a higher level in the process of becoming an occupational therapist.

| Postmodern Curriculum is one which blends process with product. It is not bound by rigid and pre-determined objectives, plans and assessment strategies. These emerge as the ‘lesson’ progresses. The curriculum responds to, grows from and seeks unpredictable challenge. The boundary between teacher and learner is flexible. It seeks to achieve within teachers and learners a deeper understanding of self, knowledge and the environment. |

Proposed Curriculum Framework

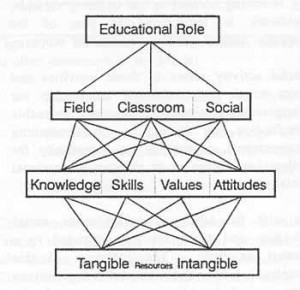

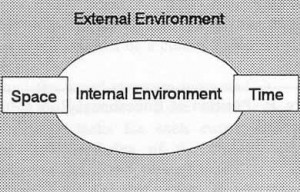

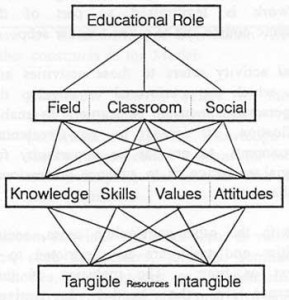

Structurally, this curriculum is viewed as an interactive, open and ‘living’ system in which there is interaction occurring within and between two immediate environments relative to a particular curriculum: the internal environment and the external environment. The internal environment is composed of the structures, conditions and influences that are found within a curriculum. These form an aggregate of educational activities and tasks. Constructs which are contained in the internal environment are: Educational Role, Curriculum Areas, Objectives of Curriculum Tasks and Resources. The lines indicate that interaction occurs between all levels of the internal environment (Fig. 1)

Figure 1: Internal Environment of the Curriculum

The external environment is composed of structures, conditions and influences that surround educational activities and tasks. The external environment may be equated with curriculum context. The interaction which occurs between all constructs within the system form an ongoing dialogue within and between the two environments. This dialogue occurs within the context of space and time (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Relationship between the internal environment, external environment, space and time.

All constructs within the system are interdependent; therefore, change which occurs in any one construct will have an impact on all other constructs.

CONSTRUCTS OF THE INTERNAL ENVIRONMENT

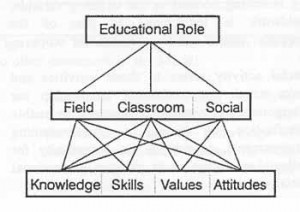

The internal environment of the curriculum in this model is composed of interactive levels. As stated earlier, these are Educational Role, Curriculum Areas, Objectives of Curriculum Tasks and Resources (See Fig. 1).

Construct 1: Educational Role

The educational role of the curriculum is determined by a number of factors including professional demand and standard, socio-political forces influencing education, history and tradition. ‘Role’ may be equated with purpose, goal or mission. ‘Role’ is used in this model because it imparts a notion of ‘character’ thus giving the curriculum ‘life’. Accomplishment of educational roles influences and is dependent on the interaction occurring between all other constructs in the model (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Position of Educational Role in the Curriculum

The curriculum may have a number of educational roles with each having an influence on the ‘appearance’ of the curriculum, that is, the pattern of emphasis placed on different constructs in the model. For example, an educational role of inspiring students to pursue learning as a lifelong aim is reflected in the type of curriculum activities planned from the different curriculum areas, the balance of objectives developed and core resources required. An educational role of preparing students for work would require a curriculum with a different ‘appearance’ to one which has a ‘liberal arts’ role.

As part of an interactive system, change anywhere can influence the degree to which an educational role is accomplished. For example, academic staff choose to influence the educational roles of the curriculum by the type activities and tasks they plan. Students may also influence the educational role through their inherent strengths and needs as a student body. The balance of educational roles held by the curriculum at any one time, the changes in roles and the abandonment or adoption of roles form transitions in the curriculum which are continually made throughout its existence.

Educational roles consist of patterns of educational behaviour designed to accomplish a broad purpose/s or curriculum aim. They are composed of configurations of activities and tasks performed in various Curriculum Areas. They are established through choice and/or need and are modified with experience, circumstance and time.

Construct 2: Curriculum Areas

Areas of the curriculum are the major classifications of educational activities and tasks carried out by teachers and learners in the curriculum to fulfil the requirements of the Educational Role (Fig. 4).

Curriculum areas are major divisions of activities and tasks which are designed to accomplish the educational role of the curriculum. They consist of Classroom activities and tasks, Fieldwork activities and tasks and Social activities and tasks.

Figure 4: Relationship of Curriculum Areas to other constructs in the Model.

| Classroom activity refers to those activities and tasks which are performed to develop knowledge of theory, classification systems for facts and principles, and frameworks for skill acquisition. |

Classroom activities and tasks occur in various forms, such as lectures, tutorials, seminars, laboratories, study groups or independently. Classroom activities and tasks may also occur off campus as during clinical placements (eg., ‘Fieldwork Lecture Series’) or in social contexts such as ‘Information nights’.

Activities and tasks may be classified as `classroom’ whenever attempts are made to direct, facilitate or collaborate with learners to enable them to acquire information for use. This definition is seen to be an important shift in definitions of what constitutes the ‘classroom’.

| Fieldwork activity refers to those activities and tasks which are performed to reinforce the practical application of theory or skills, to consolidate and integrate learning, to allow the complexity of practice to be experienced, and to encourage experimentation with a professional versus student role. |

Fieldwork activities and tasks may occur in the `field’ as in clinical placements, internships or clinical visits. Fieldwork activities may also occur in campus settings such as through structured clinical practicums which employ patients/clients as tutor assistants, various forms of simulated case study or community based data collection exercises. Similarly, aspects of fieldwork activities and tasks may occur through social activity in which discussions of fieldwork issues arise.

Activities and tasks may be described as `fieldwork’ whenever attempts are made to apply information to the direct or indirect service functions of a profession. This is seen to be an important change in definition of what traditionally has been referred to as ‘fieldwork’. By removing context as the defining variable, fieldwork is legitimised as part of the academic course and is given broader scope.

Social activity refers to those activities and tasks which are performed to develop the interpersonal dimension of learners, to enable clarification of issues in non-threatening environments, to provide an opportunity for collegial exchange or to enhance professional socialisation.

As with the other curriculum areas, social activities and tasks are not restricted to a context or time. The inclusion of this construct in the model legitimises ‘extracurricular’ activities as part of the curriculum. These ‘social’ activities have been viewed by several authors as important elements in developing a professional identity (Bailey, 1990; Brollier, 1970; Elias & Gol-Giese, 1979; Sabari, 1985). Social activities and tasks may include mentorship, group representative meetings, staff/student BBQ’s, year end reviews and professional debate clubs, as well as, cohort and group learning activities. Activities and tasks may be classified as `social’ whenever informal interaction with others, enjoyment of educational experiences and professional socialisation are the intent.

Performance of activities and tasks in each of the curriculum areas interact with and influence each other. The capacity for interaction is represented by broken lines separating the Curriculum Areas (Fig. 4). For example, the type of fieldwork activity possible depends on the amount of information acquired in classroom activities and tasks. Alternatively, fieldwork activity may make some classroom activity redundant. Social activity may influence both fieldwork and classroom performance through its contribution to the establishment of a cohort of learners.

Beyond the broad structure presented, it is not possible to generate a static classification of activities or tasks for each curriculum area based on knowledge of the activity alone. This classification process is, in part, determined by the teacher and, largely, by the learner. That is, the integration of the outcome of activities and tasks by the learner determines its classification in terms of curriculum area. One learner may perceive an experience to be a theoretical ‘classroom’ activity while another may perceive the same experience as a ‘fieldwork’ activity. Moreover, classification of the same activity or task may change from day to day. The domain into which a given activity or task falls at any given time is dependent on the intent, nature, subjective interpretation and context of the task (Chapparo & Ranka, 1992; Nelson, 1988; Christiansen, 1991).

Construct 3: Objectives of Curriculum Tasks

Activities and tasks in each of the curriculum areas are supported by the Objectives of Curriculum Tasks.

Components of Curriculum Tasks are the teaching and learning knowledge, skills, values and attitudes which support curriculum activities and tasks (Fig. 5). These components facilitate accomplishment of activities and tasks in the curriculum areas. As part of this postmodern curriculum model, they may also be determined by what occurs. For example, a planned activity or task may accomplish something totally different than intended. Similarly, an ‘objective’ may emerge through engagement in unplanned activities or tasks.

| Knowledge Component: is that aspect of a curriculum activity or task which focuses on transmitting factual information, facilitating an understanding of theory, creating conceptual images of practice. |

| Skill Component: is that aspect of a curriculum activity or task which focuses on applying theory, developing abilities or establishing proficiency in performance. |

| Attitude Component: is that aspect of a curriculum activity or task which focuses on discussing and encouraging the organisation of beliefs around an aspect of practice and examining the impact of attitudes on practice. |

| Value Component: is that aspect of a curriculum activity or task which focuses on the discussing the perceived worth of an aspect of practice and examining the impact of values on practice. |

Figure 5: Relationship of the Objectives of Curriculum Tasks to other constructs in the Model.

As with activities and tasks in the Curriculum Areas, the ‘knowledge’, ‘skill’, ‘attitude’ and ‘value’ components of various curriculum activities and tasks interact with and influence each other. For example, knowledge acquired through participation in any one activity or task may influence the degree of skill development which occurs; Attitudes may influence one’s receptivity to knowledge; values may influence the degree of skill acquisition which occurs; and acquisition of skills may influence knowledge, attitudes and values. This is reflected by the broken lines contained within Level 3 of the Model (Fig. 5).

Construct 4: Resources

This construct identifies the core of the curriculum as being it’s resources. Core resources form the foundation on which all other aspects of the model depend (Fig. 6).

Resources: are the tangible and intangible inputs the curriculum requires to survive.

The identification and separation of resources into core elements which are tangible (with physical properties) and those which are intangible (without material existence) is a significant aspect of this model. This classification recognises that the curriculum has a tangible core, or `body’, and an intangible `mind’ and `spirit’. Both are equally important in maintaining the ‘health’ of the curriculum.

igure 6: Relationship of Resources to other constructs in the Model.

| Tangible resources are core elements which have physical properties. They include people, and the equipment, tools, and materials people use to obtain and convey information. |

‘People’ include academic staff, support staff and students, and are the most important resource for obvious reasons. An important aspect of this dimension of the model is recognition of ‘support staff’ as a legitimate part of the curriculum. It acknowledges that a change in support staff may have profound effects on the curriculum. Equipment, tools, and materials are also important. It might be suggested that people can function without these tangible resources. To some extent this is true. However, it must be considered that humans are `tool makers’ and `tool users’. Even the most primitive societies ‘teach’ with tools (Goodall, 1986; Knudtson & Suzuki, 1992).

| Intangible resources are core elements which are without material existence. They are products of the mind and spirit of people, and are reflected in the energy, commitment, enthusiasm and ideas they bring to the curriculum. |

These intangible elements are essential for the curriculum to succeed. They give the curriculum it’s personality, creativity, flexibility and drive. The degree to which these intangible elements are able to prompt such behaviours as exploration, development, adaptation and change determines the energy of the curriculum. Stimulation of these intangible resources in teachers and learners is the ultimate challenge of the curriculum.

Bess (1982), Czikszenthmihalyi, 1982; Deci and Ryan (1982), Hall and Bazerman (1982), McKeachie (1982) and Sherman, Armistead, Fowler, Barksdale and Reif (1987) emphasise the importance of challenge and recognition in maintaining a ‘motivation’ to teach in academics. Support staff ‘motivation’ also contributes to the ‘personality’ of the curriculum.

Biggs (1987) and others (Dart & Clarke, 1991; Entwistle, & Ramsden, 1983; Watkins, 1983) stress the importance of ‘deep learning’. Accomplishment of ‘deep learning’ in teachers and learners is the aim of this curriculum and depends on the degree to which the intangible resources of energy, commitment, enthusiasm and creativity are active. Czikszenthmihalyi (1975) discusses the concept of “flow” in which skill and challenge are matched to the extent that the person (learner) is “lost” in what they are doing (learning). This, too, is partly dependent on the ‘creative’, ‘enthusiastic’ and ‘individualised’ character of the curriculum.

These tangible and intangible resources interact and influence each other as well as exerting influence on other levels of the model (Fig. 6). For example, people may function as teachers, learners or a member of support staff. Students and staff may identify themselves interchangeably (eg. students photocopy reference material for a class; support staff learn about occupational therapy). The amount of tangible resources available may influence the spirit and enthusiasm of academic staff (intangible resources). An absence of tangible resources (overhead projector) may require teachers to be creative (intangible resource) in providing verbal descriptions to learners.

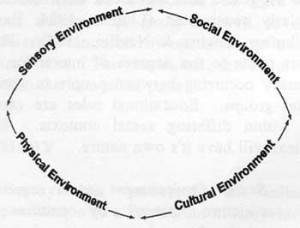

Construct 5: External Environment

The external environment is conceptualised as being composed of structures, conditions and influences that surround educational activities and tasks, and in which educational roles are performed (Fig. 7). It is an inherent part of the curriculum. Although aspects of the external environment have been artificially separated in this model, the environment is an interactive whole which has physical, sensory, social and cultural dimensions as indicated by the arrows. The interaction between these dimensions creates further subdivisions which include political and economic aspects of the environment although these are not illustrated in the Model.

Figure 7: The External Environment of the Model

External Environment is the educational context. This context has physical, sensory, social and cultural dimensions.

The physical environment consists of the physical structures which house the curriculum. Examples of these physical structures might include classrooms, field sites, picnic grounds. They may be constructions, such as buildings or natural surroundings.

| Physical Dimension is the natural or constructed surroundings in which curriculum activities and tasks occur. They form physical boundaries and contribute to shaping learner/teacher behaviour and are also influenced by it. |

The sensory environment takes into consideration the sensory nature of the context. This includes aspects of temperature, lighting, sound, spatial aspects of room construction and furniture arrangement, visual ‘aesthetics’ and odours. It has profound effect on attention and receptivity to learning.

| Sensory dimension is the sensory surroundings in which curriculum activities and tasks occur. They provide a sensory overlay to physical dimensions of the environment and contribute to shaping learner/teacher behaviour and are also influenced by it. |

The curriculum is social in nature. Just as the internal environment is conceptualised as being composed of differing levels, some theorists have suggested that the social environment is similarly constructed (Llorens, 1984, Barris, Kielhofner, Levine & Neville, 1985). These layers relate to the degrees of interaction and intimacy occurring between people in various social groups. Educational roles are carried out within differing social contexts. Each context will have it’s own nature.

| Social Environment is an organised structure created by patterns of relationships between people who function in a group in the curriculum. This in turn contributes to establishing the boundaries of behaviour. The social environment may also change as a result of the behaviour of people. |

Culture here refers to learned patterns of behaviour shared by members of a group which provide them with effective mechanisms for interaction (Krefting & Krefting, 1991). Culture is an overriding concept but numerous sub-cultures may be identified that relate to specific groups in specific educational environments; for example, classroom culture, university culture. Each culture has its own beliefs and rituals that influence behaviour.

| Cultural environment is an organised structure composed of systems of values, beliefs, ideals and customs which contribute to shaping behaviour and are also influenced by the behaviour of a person or a group of people. |

Consistent with other aspects of the system, these environments influence each other and the ‘internal environment’. The internal environment places adaptive demands on the ‘external environments’. For example, a physical environment will contribute to shaping the social interaction possible. People (core resource) and the social environment they create, will change the physical environment to meet their needs. Culture will influence the physical structures and patterns of interaction occurring.

Similarly, these environments influence the activities and tasks (curriculum areas), ‘components’ and ‘core elements’ seeking to accomplish an educational role. For example, a physical lack of fieldwork clinical sites will place demands on all other elements. The social environment of the classroom will place demands on the teacher in terms of the components of curriculum tasks established or activities and tasks planned. Again, the reverse is also true. The ‘internal’ elements contribute to changing the ‘external’ elements by the very nature of their existence. The internal elements become a part of the external environment.

Construct 6: Time & Space

As a living system possessing a `body’, `mind’, `spirit’ and `house’, this curriculum occupies a space and changes over time. Time and Space are illustrated in the schematic diagramby grey shading (Fig. 8) .

Figure 8: Time and Space of the Model

This shading portrays time and space as crossing all dimensions of the internal and external environment.

The curriculum is a complex, interactive structure which occupies a space but the absence of a border suggests that space is limitless. This allows the curriculum to be as expansive as required and exist as part of a larger system in space.

| Space is a composition of real or imagined matter that ‘occupies’ a place, eg. the curriculum has its space. |

Time is another important characteristic of thiscurriculum model. A temporal order exists in several dimensions of the curriculum, including decisions about the amount of time devoted to performance in each area, when activities and tasks occur, what happened previously and what is projected for the future. The temporal dimension gives structure to the life of the curriculum.

| Time is the temporal ordering of events that can be observed or imagined. |

Together, ‘space’ and ‘time’ consider that interactions which occur between constructs can reorganise the curriculum form (space) at any point (time). This suggests that the curriculum can be considered to have a previous existence (a past), as well as an unpredictable future and it can never go back to what it was. The curriculum, therefore, is more than the sum of its parts.

SUMMARY

This essay has presented an initial conceptualisation of a curriculum model which is based on postmodern views of existence and an emerging model of occupational therapy practice (Chapparo & Ranka, 1992).

The curriculum model presented (Appendix 1) is a multifaceted matrix which contains multiple, interacting levels. These have been described as existing in an ‘internal’ environment and an ‘external’ environment. The interactive structure allows for change to arise from anywhere in the model and effect the entire system. These stimuli for change are viewed as perturbations which prompt the system to reorganise itself on a higher level or to transform itself into something different. This model also acknowledges that boundaries between aspects of each level are artificial, all constructs are ‘entwined’. It identifies that the purpose of the curriculum is its educational role and that the degree to which this role can be accomplished depends on core elements of tangible and intangible resources. If these resources are depleted, ‘entropy’ will occur.

Further development of the model will focus on refinement of descriptions of the constructs and their interaction, elaboration of examples of their interaction and the application of specific teaching and learning principles from areas such as self-directed learning, adult learning and lifelong learning within the structure of this model.

REFERENCES

American Occupational Therapy Association, Inc. (1974). A curriculum guide for occupational therapy educators. Rockville, MD: Author

Aronowitz, S., & Giroux, H. (1991). Postmodern education, politics, culture and social criticism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Bailey, D. (1990). Reasons for attrition from occupational therapy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 44(1), 23-29.

Bain, W.J. (1991). Toward a postmodern politics: Knowledges and teachers. Educational Foundations, 5(1), 89-107.

Barris, R., Kielhofner, G., Levine, R.E., & Neville, A.M. (1985). Occupation as interaction with the environment. In G. Kielhofner (Ed.), A model of human occupation: Theory and application (pp 42-62). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

Bateson, G., (1979). Mind and nature: A necessary unity. New York: E.P. Dutton

Berlin, J.A. (1992). Poststructuralism, cultural studies and the composition classroom: Postmodern theory in practice. Rhetoric Review, 11(1), 16-33

von Bertalanffy, L. (1971). General systems theory. London: Allen Lane. (Original work published 1926).

Bess, J.L. (1982). Editor’s notes. In J.L. Bess (Ed.)., New directions for teaching and learning, No. 10: Motivating professors to teach effectively. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Biggs, J.B. (1987). Student approaches to learning and studying. Hawthorne, Vic: ACER

Broffenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and by design. Cambaridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Brollier, C. (1970). Personality characteristics of three allied health professional groups. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 24, 500-506.

Carter, B. (1993). Losing the common tough: a post-modern politics of the curriculum? Curriculum Studies, 1(1), 149-155.

Chapparo, C., & Ranka, J. (1992). Occupational performance model. Draft Manuscript. (Available from authors, School of Occupational Therapy, The University of Sydney, PO Box 170, Lidcombe, NSW, Australia, 2141.

Christiansen, C. (1991). Occupational therapy: Intervention for life performance. In C. Christiansen, & B. Baum, Occupational therapy: Overcoming human performance deficits. Thorofare, NJ: Slack

Creek, J. (1990). The knowledge base. In J. Creek (Ed.) Occupational therapy and mental health: principles, skills and practice. Edinburh: Churchill Livingstone.

Czikszenthmihalyi, M. (1982). Intrinsic motivation and effective teaching. In J.L. Bess (Ed.), New directions for teaching and learning, No. 10: Motivating professors to teach effectively. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Czikszenthmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and anxiety: The experience of play in work and games. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Dart, B.C., & Clarke, J.A. (1991). Helping students become better learners: a case study in teacher education. Higher Education, 22, 317-335.

Deci, E.L., & Ryan, R.M. (1982). Intrinsic motivation to teach: Possibilities and obstacles in our colleges and universities. In J.L. Bess (Ed.)., New directions for teaching and learning, No. 10: Motivating professors to teach effectively. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Doll, W.E., Jr. (1989). Foundations for a post-modern curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 21(3), 243-253.

Elias, M., & Gol-Giese, A. (1979). A question of professional boundaries: Implications for educational programs. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 33(3), 175-179.

Entwistle, N.J., & Ramsden, P. (1983). Understanding student learning. London: Croom Helm

Gardner, H. (1985). The mind’s new science. New York: Basic Books

Giroux, H. (1988). Postmodernism and the discourse of educational criticism. Journal of Education, 170(3), 5-30.

Giroux, H. (1990). Curriculum discourse as postmodernist critical practice. Geelong, Australia: Deakin University Press.

Goodall, J. (1986). The chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of behaviour. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University

Griffin, C. (1983). Curriculum theory in adult and lifelong education. London: Croon Helm

Grundy, S. (1987). Curriculum: Product or praxis. London: The Palmer Press.

Hall, D.T., & Bazerman, M.H. (1982). Organization design and faculty motivation to teach. In J.L. Bess (Ed.)., New directions for teaching and learning, No. 10: Motivating professors to teach effectively. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Hlynka, D. (1991). Postmodern excursions into educational technology. Educational Technology, 31(6), 27-30.

Hollis, V. (1991). Self-directed learning as a post-basic educational continuum. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 54(2), 45-48.

Jacobs, T., & Lyons, S. (1992). Give me a fish and I eat today: teach me to fish and I eat for a lifetime: The Newcastle programme. Australian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 39(1), 29-32.

Jantzen, A. (1977). A proposal for occupational therapy education. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 31(10), 660-665.

Kielhofner, G. (1985). A model of human occupation: theory and application. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

Kitwood, T. (1990). Psychotherapy, postmodernism and morality. Journal of Moral Education, 19(1), 3-13.

Knowles, M.S. (1973). The adult learner: A neglected species. Houston: Gulf Publishing Co.

Krefting, L. (1985). The use of conceptual models in clinical practice. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 52(4), 175-178.

Krefting, L., & Krefting, D.V. (1991). Cultural influences on performance. In C. Christiansen, & B. Baum, Occupational therapy: Overcoming human performance deficits. Thorofare, NJ: Slack

Knudtson, P., & Suzuki, D. (1992). Wisdom of the elders. Toronto: Allen, & Unwin

Leonardelli, c.a., & Gratz, R. (1986). Occupational therapy education: the relationship of purpose, objectives and teaching models. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 40(2), 96-102.

Llorens, L.A. (1984). Changing balance: Environment and individual. American Journal of Occupational Therapy,38, 29-34.

McCracken, T. (1989). Between language and silence: Postpedagogy’s middle way: Part 1 the text. Educational Resources Information Centre (ERIC), ED 307630

McKeachie, W.J. (1982). The rewards of teaching. In J.L. Bess (Ed.)., New directions for teaching and learning, No. 10: Motivating professors to teach effectively. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass

Mosey, A.C. (1986). Psychosocial components of occupational therapy. New York: Ravens Press

Mularski, C.A., Nystrom, E., & Grant, H.K. (1989). Developing information-seeking skills in occupational therapy students. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 41(9), 555-561.

Neistadt, M. (1987). Classroom as clinic: A model for teaching clinical reasoning in occupational therapy education. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 41(10), 631-637.

Nelson, D. (1988). Occupation: Form and performance. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 42(10), 633-641.

Newton, I. (1972/1729). Mathematical principles of natural philosophy. Cambridge, Ma: Harvard University Press.

Pelland, M.J. (1987). A conceptual model for the instruction and supervision of treatment planning. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 41(6), 351-359.

Piaget, J. (1977). The development of thought. New York: Viking Press.

Prigogne, I. (1980). From being to becoming. San Francisco: W.W. Freeman

Prigogne, I., & Stengers, E. (1984). Order out of chaos. New York: Bantam Books

Ranka, J., Twible, R., & Pitkeathly, P. (1991, September). Lifelong information?seeking skills: A curriculum initiative. Paper preesnted at The 16 Federal Congress of the Australian Association of Occupational Therapists, Adelaide

Reed, K. (1984). Models of practice in occupational therapy. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins

Reilly, M. (1958). An occupational therapy curriculum for 1965. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 12, 293-299.

Reilly, M. (1969). The educational process. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 23, 299-307.

Rogers, J. (1980a). Design of the master’s degree in occupational therapy, Part 1: a logical approach. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 34, 113-118.

Rogers, J. (1980b). Design of the master’s degree in occupational therapy, Part 1: an empirical approach. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 34, 176-184.

Rogers, J. (1983). Eleanor Clark Slagle lecture — 1983. Clinical reasoning: The ethics, science and art. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 37, 601-616.

Sabari, J. (1985). Professional socialization: Implications for occupational therapy education. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 39(2), 96-102.

Sameroff, A.J. (1982). Development and the dialectic: The need for a systems approach. In A.W. Collins (Ed.), The Minnesota symposium on child psychology (Vol.15). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum

Schemm, R.L. (1993). Curriculum based on systems theory. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 47(7), 625-634.Sherman, T.M., Armistead, L.P., Fowler, F., Barksdale, M.A., & Reif, G. (1987). The quest for excellence in university teaching. Journal of Higher Education, 48(1), 66-81.

Smith, R.M. (1983). Learning how to learn. Milton Keynes, England: Open University Press.

Townsend, E., Brintnell, s., & Staisey, N. (1990). Developing guidelines for client-centred occupaptional therapy practice. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 57(2), 69-75.

Tyler, R.W. (1949). Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tyler, R.W. (1979). Toward improved curriculum theory: The inside story. Curriculum Inquiry, 9, 251-256.

Waters, B. (1986). Ministry and the University in a post-modern world. Religion and Intellectual Life, 4(1), 113-122.

Watkins, D. (1983). Depth of processing and the quality of learning outcomes. Instructional Science, 12, 49-58.

Whitehead, A. (1969/1929). Process and reality. New York: The Free Press

Zais, R.S. (1976). Curriculum: Principles and foundations. New York: Harper & Row

APPENDIX 1:

A Curriculum Model for Occupational Therapy Education

based on a synthesis of Postmodern views and the

Occupational Performance Model (Chapparo & Ranka, 1992)