Kylie Wilkinson, Christine Chapparo

Kylie Wilkinson BAppSc(OT)(Hons), at the time of writing this paper was an occupational therapist working with the Commonwealth Rehabilitation Service. This paper contains work that was generated as part of her honours thesis, completed in the School of Occupational Therapy, The University of Sydney

Christine Chapparo MA,DipOT,OTR,FAOTA is a senior lecturer at the School of Occupational Therapy, The University of Sydney

Children with severe and multiple disabilities “constitute a substantial portion of the total occupational therapy population” (Clancy & Clarke, 1990,p.162). As members of most therapy and educational service delivery teams, occupational therapists are often asked to assume prominent roles in designing and implementing therapeutic programs for these children. Although they are often classified according to their sensory, motor or intellectual impairment, they are regarded by occupational therapists as first and foremost whole, multifaceted individuals with unique existence in the social and physical world (Nelson, 1984). Each child’s developmental needs are broad, deep and complex, radiating into all aspects of occupational performance. While improving performance of occupational tasks in areas of self-maintenance, school, play and rest are important concerns, establishing an occupational identity through occupational roles, is considered fundamental to occupational therapy intervention for children with multiple disability.

One proposition implicit in the Occupational Performance Model (Australia) (Chapparo & Ranka, 1996) is that the role of player, with its associated play behaviours and component elements, is a primary occupational role of children. Of the broad categories of occupational performance, play is particularly deficient in most children with developmental disability (Nelson, 1984). Reportedly, children with multiple sensory, motor and intellectual disabilities have difficulty developing and engaging in play behaviours due to a variety of deficits. Whereas school and self-maintenance tasks can be taught in a systematic fashion, play does not appear to change in response to similar instructional strategies. Nelson (1984) hypothesises that this is due to the nature of play itself, the essential component of which is that it is not directed by others. Similarly, various researchers have found that cognitive, sensorimotor and perceptual component deficits are not able to account for deficient play performance in populations of children with multiple developmental disabilities. Moreover, current assessment tools available to occupational therapists are unable to describe play patterns and play deficits in children with developmental disorders (Bundy, 1991; Parham, 1992). Behaviours which appear to interfere most often with their ability to perform play and school tasks include diminished attention to the environment, high levels of stereotyped or self-absorbed behaviour, passivity, lack of initiative and poor self expression (Nelson, 1984).

Given that play is a complex phenomenon and that occupational therapists consider play to be a primary occupational role of childhood (Reilly, 1974; Fisher, Murray & Bundy, 1991; Keilhofner, 1985; Pratt, 1989), few occupational therapy researchers or theorists have examined play in terms of the performance components that underlie it (Morrison, Bundy & Fisher, 1991). Fewer still have examined play deficits which exist in children with multiple disabilities, or have sought to determine styles of occupational therapy intervention that are effective in facilitating playfulness.

Therapists who work with children who have disabilities adopt three approaches to direct intervention to improve play responses. First, the most traditional form of therapy advocates the development of adaptive play skills through the use of play tasks that are directed by the therapist (Blanche, 1992; Demchak, 1990; Gallagher & Berkson, 1986; Geniale et al, 1986; Josefowicz, 1980; Penso, 1987; Riley, 1980; Sent & Marks, 1989; Vassallo, 1986). Second, therapists who work specifically with children who have visual and hearing impairments apply additional visual and auditory stimulation during play occupations to assist the child to be more aware of and responsive to the environment (Alice Betteridge School, 1988; Allard, 1983; Anderson et al, 1987; Armstrong & Rennies, 1986; Blanksby, 1992; Caplan & Caplan, 1974; Cummings, 1989; Erhardt, 1987; Freeman, 1975; Goetz & Gee, 1987; Lee, 1977; Michelman, 1971; Pratt & Allen, 1989; Snow, 1989; Stewart et al, 1991). Third, and more recently, therapists employ added touch and movement stimulation that is embedded in play occupations through the use of sensory integrative procedures (Ayres, 1979; Arendt et al, 1988; Clark, Mailloux & Parham, 1989; Fisher, et al, 1991; Kanter et al, 1982; Kimball, 1988; Nelson, 1984; Ottenbacher & Short, 1981; Pratt & Allen, 1989). Additionally, children seek play during solitary times and it is during this type of play that environmental properties are learned and mastery of the environment during play is reinforced (Lehrer, 1981).

These three models of intervention and as well as solitary play all lie within the following general principles of occupational therapy and occupational performance specifically (Christiansen, 1991):

| The child is viewed as an active participant in developing an occupational identity | |

| 2) | The occupational therapist is viewed as facilitator or teacher |

| 3) | The intervention setting is viewed as an environment for developing occupational performance skills and roles |

| 4) | Occupation is the preferred intervention medium |

There is no consensus to be derived from research studying the effectiveness of any of these three therapy interventions for children with developmental disabilities. While some reports suggest that sensory integration is able to elicit better adaptive responses than control models (Chapparo, Hummell, Macmillan, & Rumble, 1991), other reports contradict these findings. Many of these studies have employed large numbers of children involving comparative groups research designs and reviews of these studies are commonly characterised by criticisms of methodology (Cermack & Henderson, 1990).

Suggestions for more appropriate directions for research have included tailoring research designs to reflect the individual nature of the therapy and to the development of methods to measure small changes in behaviour that are both relevant and important to the child’s occupational performance (Cermack & Henderson, 1990; Ottenbacher, 1991). Cermack and Henderson (1990), for example proposed that research into the effects of sensory integrative procedures involve assessment areas not traditionally measured such as play skills, attention, affect and exploratory behaviour.

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY

The purpose of this study was to determine:

1) The immediate effect of sensory integrative procedures; adaptive play; and play using additional auditory/visual stimulation during therapy on the following components of self-directed play responses in children with multiple sensory, motor and intellectual disabilities:

| a. | time spent and amount of vocalisation |

| b. | duration of enjoyment |

| c. | time spent in on-task play behaviour (attention) |

| d. | time spent in non-participatory intermission behaviour (passivity) |

| e. | time spent in self absorbed and stereotypic behaviour |

RESEARCH DESIGN

This study used a repeated measures within subject single system design with multiple measures across multiple subjects (Ott, 1988; Ottenbacher, 1986). In this design, the intervention is introduced after a baseline has been established. Each participant is then randomly exposed to each of the treatments a set number of consecutive times. The random order controls for carryover effects where it is not possible to withhold treatment to allow washout of previous treatments. To best demonstrate effect, three children were studied. This allowed a maximum number of controls to be applied within the time constraints of the researchers.

METHODS

Subjects

Three children with visual, hearing, motor and intellectual deficits served as subjects (C1, C2, and C3). Two were aged 8 and one 7 years, all were male and attended the same special school for children with visual and hearing impairment. Each child had observable deficits in play behaviours relative to their age and school/family expectations that were characterised by poor attention span, poor initiation of play activity, stereotypic and self-absorbed behaviours. Two children communicated through words, although at low level, one child communicated primarily through vocalisations, eye gaze and other gestures. All three children were familiar with the therapist who carried out the interventions. Detailed descriptions of each child were constructed prior to beginning the study from therapy reports, and observations of therapy and classroom performance. The detailed descriptions were then used to determine the play variables that were to be studied.

Definition of variables

| a. | Sensory integration procedures. |

| Sensory integration involves receiving and processing of sensory information for use (Ayres, 1972) to promote the output of adaptive behaviour such as play. For the purposes of this study, sensory integrative procedures were operationally defined as play activity negotiated between therapist and child that incorporates sensory stimulation through the use of specialised therapy equipment such as swings, bolsters, and moveable surfaces. | |

| b. | Adaptive play procedures. |

| Play activity that involves the child playing with a number of familiar and liked activities with direction and help from the therapist. Direction and help is in the form of verbal direction and positioning. The procedures did not include sensory integrative equipment. | |

| c. | Play with additional auditory/visual stimulation. |

| Play activities with a set number of familiar and liked activities with additional visual and auditory stimulation provided by tapes of age appropriate music and videotaped moving pictures that changed format every 30 – 60 seconds. The treatment setting did not include touch and movement stimulatory equipment. | |

| d. | Solitary play. |

| Play activities with a set number of familiar and liked activities positioned so that the child could make an active choice. The therapist was not present to give direction, and the child was not able to interact with any specialised therapy equipment. | |

The following responses were measured and have been operationally defined as:

| a. | Vocalisation: (V) |

| Any available vocal sound produced from a single breath that was not characteristic of simple respiration. Excluded were coughs and hiccups. Included were words, work-like utterances, grunts, coos, squeals, and laughs (Hilke, 1987) | |

| b. | Attention to play as measured by on-task behaviour: (OTB) |

| The child actively attended to and worked on a task chosen, asked for , or given to them by the therapist. This may have been evidenced by looking at the task, looking at the therapist, manipulating objects, purposeful task related body movement, and seeking behaviours to extend play or prolong play. | |

| c. | Non-participatory intermission time behaviour: (NPIT) |

| Passive behaviour that was not purposefully task oriented, interacting with the therapist or actively seeking a new task to do. Self absorbed behaviour and enjoyment responses were not included as non-participatory intermission time. | |

| d. | Self absorbed or stereotypic behaviour:(SSB) |

| Responses of self-injurious behaviour such as head banging, eye poking, hand mouthing, slapping and head or hand shaking, rocking, swaying, posturing, and any other idiosyncratic repetitive, patterned, nonlocomotor movement. | |

| e. | Indications of enjoyment:(E) |

| isolated laughter, smiles and sudden glee. | |

ADMINISTRATION OF THE INTERVENTIONS

Sequence

The multiple baseline design consisted of 4 phases.

| Phase 1 Baseline: | The child was observed for up to six 20 minute sessions in solitary play with toys, without therapy involvement and no additional pieces of therapy equipment. |

| Phase 2: | The child participated in adaptive play which was directed by the therapist for six consecutive 20 minute sessions. |

| Phase 3: | The child participated in play activity that incorporated sensory integrative procedures for six consecutive 20 minute sessions. |

| Phase 4: | The child participated in play activity that incorporated additional visual/auditory stimulation for six consecutive 20 minute sessions. |

All children started with the baseline phase that involved solitary play, after which the children received the three interventions in varying order. This variation was used to control for changes being attributed to possible sequential effects of previously administered interventions. While it is recognised that there are 6 possible alternative intervention orders, only three have been used in this study due to time constraints of the children and the researchers. This was considered sufficient to demonstrate that a particular intervention had a consistent effect.

Therapist

One therapist administered all interventions. She was experienced in handling children with multiple sensory and motor disorders, and experienced in all the interventions offered. The therapist was not aware of the behaviours that were to be measured from videotaped records of the treatment sessions.

DATA COLLECTION SOURCES

Data was taken from two data sources at each treatment session. First, a videorecording was made of the session using simultaneous recording from two videocameras. This enabled the researchers to obtain close-up recording of the child’s face and body reactions as well as recording of the therapy events involving the therapist and equipment. Second, notes of each therapy session were kept, providing a description of any confounding events that occurred. In the opinion of the treating therapist, the effects of the presence of videocameras on the child’s reactions to intervention were unnoticeable and not confounding.

DATA CODING AND RECORDING PROCEDURES

As there are no standardised tests for the variables measured, data was collected using continuous recording of events (Mann, Have, Plunkett & Meisels, 1991). The rationale for choosing this specific technique is its record of acceptable interrater reliability (Eckerman et al, 1989). This method has been shown to be more accurate in reporting behaviours than time sampling with fixed intervals (Mann et al, 1991).

Validity and reliability of measures used

The recording methods used have established validity through their repeated use in research projects that measure or describe childrens’ play behaviours or the specific variables identified (Bright et al, 1981; Eckerman et al, 1989; Hilke, 1988; Mason & Iwata, 1990; Ottenbacher, 1983).

DATA ANALYSIS

Reliability of data analysis methods used

To enhance the reliability of data analysis, the following controls were imposed:

| a) | Information of target behaviours were identified and operationally defined (Ottenbacher, 1988). |

| b) | To avoid pseudoconfirmation of results, reliability checks were performed by trained independent observers who also rated each child’s performance randomly for at least 1/3 of the data collected. This was equally distributed across experimental conditions to enable interrater reliability checks across the course of the investigation. Different raters were assigned to each phase to prevent bias over different phases. |

| c) | To prevent observer drift (Kazdin, 1982), the independent observers did not receive feedback on the reliability of scoring and were unaware of the purpose of the research. |

| d) | Intrarater reliability was conducted on 1/3 of the data. This was possible as all sessions were stored on videotape. |

Interrater and intrarater reliability were obtained using SPSS (1990) intraclass correlation coefficient computer package. Total reliability measures were used for each corresponding session of treatment because continuous sampling was used. While this is not a conservative measure, it is considered appropriate where overall duration is used to measure the dependent variable (Lagrow & Prochnow-Lagrow, 1983). The results of this analysis ranged from .80 to .99, demonstrating high levels of interrater and intrarater agreement.

Validity

To enhance internal and external validity of the study, the following controls were imposed:

| a) | The repeated measure design across subjects allowed for the systematic replication of intervention effects. |

| b) | Bias was reduced by independent data checks. |

| c) | The threat of multiple intervention interference was minimised by changing the order of the intervention phases for each child. |

| d) | Maturation was controlled for by using short term intervention phases, measuring immediacy of response and applying the interventions in different order for each child. |

| e) | Novelty was controlled by using a therapist with whom all children were familiar. |

| f) | Although inability to generalise findings is a weakness of this design, enough detail exists in this report for others to replicate the study (Hacker, 1980). |

| g) | Although interpersonal interaction between therapist and child is assumed to be the same for all interventions, it was recognised that there may have been an unconscious occurring. McReynolds and Thompson (1986,p.202) state “it is essential that experimenters provide evidence that treatment was administered as described”. In this study, two sessions from each of the interventions were observed and described by independent raters. They were then asked to compare the definitions of the individual interventions to the descriptions of intervention observed and comment on the accuracy of treatment administration. The validity of the content of interventions was confirmed. |

Data Analysis Methods

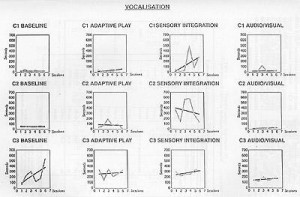

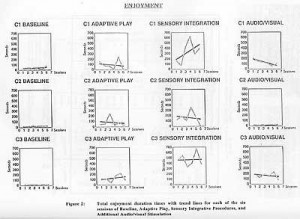

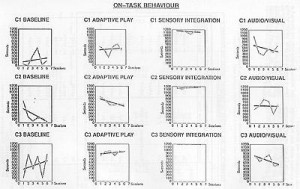

An autocorrelation coefficient of adjacent data points of less than .82 in all phases was obtained indicating the absence of significant serial dependency (Ottenbacher, 1986). Visual and statistical analysis was then applied to the data (Figures 1 – 5).

Initially, visual interpretation of the data was undertaken to determine whether differences occurred in behavioural outcomes due to immediate effects of the three interventions. Where appropriate, this consisted of looking at the level, variability, slope, mean and trend of the data.

Statistical analyses were then performed for the following reasons:

| a) | baseline data were found to be unstable |

| b) | there was a large amount of intrasubject variability |

| c) | small improvements not detectable by visual analyses alone may have been significant |

Non-parametric tests were employed. As there were four levels of within subject measurements in the repeated measures design, a Friedman two way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using ranks was first computed to determine the presence of significant difference between the three interventions and the baseline phase (SPSS,1990). Two level Wilcoxon signed-ranks tests were then used to discover the source of significant difference between each of the four phases in comparison to the others (Tables 2,4,6,8 and 10).

RESULTS

In this paper, selected results of the visual and statistical analyses are outlined for each of five dependent variables: vocalisation, enjoyment, on task behaviour, non participatory intermission time and self absorbed behaviour. For each behaviour, visual analyses will be presented followed by statistical analysis. Although selected results only are highlighted and discussed, all data generated are available to the reader on figures and tables accompanying each variable result.

Vocalisation (V)

Visual Analysis

Across the four phases for each of the three children in the study, sensory integrative procedures produced the highest mean duration of vocalisation (Table 1). There was no consistency in the slope of the trend line for any of the interventions shown (Figure 1). Differences in levels, as listed in Table 1, were greatest in C1 and C2 for sensory integrative procedures in comparison to other procedures and greatest in C3′s adaptive play and sensory integrative procedures than the other two phases. Data was variable across the three children and across the four treatments as can be seen in Table 1. While it is optimal to achieve high variability scores (above 85%) to demonstrate consistent outcomes of treatment, the scores are still clinically useful in this study. All three children had multiple disabilities characterised by emerging behaviours and their behaviour in everyday situations as well as therapy was variable.

Statistical Analysis (Vocalisation)

As shown in Table 2, no consistent significant differences occurred between individual treatments across all three children when the Wilcoxon signed ranks tests were computed. For C1, sensory integrative procedures had a greater immediate effects on vocalisation than did adaptive play. Sensory integrative procedures also produced greater immediate effects in comparison to additional audio/visual sensory stimulation and baseline freeplay scores for C2. Additional audio/visual sensory stimulation produced a greater immediate effect on vocalisation than freeplay but less than the immediate effects of adaptive play. For C3, both adaptive play had greater immediate effects on vocalisation than additional audio/visual stimulation. All other differences noted visually were not statistically significant.

Enjoyment (E)

Visual Analysis

Of the enjoyment measures for each of the four phases shown in Figure 2, sensory integrative procedures consistently produced the highest immediate treatment effects. This is depicted by the highest mean levels and the highest individual treatment value for enjoyment being found in sensory integrative procedures for C1, C2 and C3 (Table 3). Table 3 shows slope and trend to be inconsistent across phases and children, with all three children showing the greatest slope in different intervention phases.

Statistical Analysis

For each child, sensory integrative procedures achieved an acceptable level of significance with a higher immediate effect on enjoyment than baseline freeplay for C1, C2 and C3 (Table 4). The Wilcoxon signed-ranks tests revealed sensory integrative procedures to be the intervention phase that facilitated the greatest amount of enjoyment in comparison to other treatments (Table 4), except for adaptive play (C2) and audio/visual stimulation (C1).

On Task Behaviour (OTB)

Visual Analysis (Figure 3)

On task behaviour as shown in Figure 3 and Table 5, recorded the highest mean duration score during the sensory integration phase of intervention. For C1 and C2, this immediate effect on on task behaviour was almost 100% greater than all other interventions. Adaptive play for C2 and C3 and audio/visual stimulation for C1 produced the second highest immediate effects on on task scores. The lowest scores were consistently baseline freeplay phases in both children possibly showing the difference in therapist child interaction in comparison to a non-therapist situation.

Slope, as with other behaviours measured, is inconsistent. The level between sensory integrative procedures and all the other phases was always the highest at the beginning of sensory integration phases as seen in Table 5. 100% variability was scored for sensory integrative procedures for each of the three children, and scores show values close to the full twenty minutes time period for each child.

Statistical Analysis (On task behaviour)

The only significant results from the ANOVA in Table 6 is for C3 with sensory integrative procedures resulting in a higher level of on task behaviour than baseline freeplay. C1 and C2 had similar results with levels approaching significance.

The Wilcoxon signed-ranks test presented in Table 6 supports the visual analysis whereby sensory integrative procedures produced the greatest immediate effect on on task behaviour in comparison to other treatments across all three children.

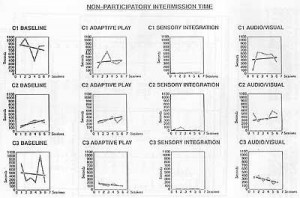

Non Participatory Intermission Time

Visual Analysis (Figure 4)

Sensory integrative phase mean scores for immediate effects on non participatory intermission time was the lowest of all interventions across the four phases (Table 7).

Each of the three children achieved an optimal score of zero passivity (NPIT) during sensory integrative procedures. This score was not achieved during any other intervention.

Statistical Analysis (NPIT)

The immediate effects of sensory integrative procedures were significant, producing the lowest level of non participatory intermission time across all three children in comparison to baseline phases (Table 8). After application of the Wilcoxon signed-ranks tests to the data, sensory integration was found to produce the lowest significant difference across all treatments in all children. Significant differences were found also in C2 between adaptive play and baseline freeplay.

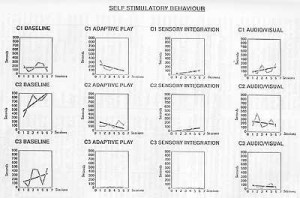

Self Absorbed and Stereotypic Behaviour (SSB)

Visual Analysis (Figure 5)

The lowest mean score of self absorbed and stereotypic behaviour (SSB) as seen in Table 9 was produced during the sensory integration phase of intervention. The most negative slopes were found in C1 and C2 during adaptive play and during the additional audio/visual stimulation phase for C3 (Figure 5). This shows beneficial trend lines for these interventions even though the interventions show higher means than the sensory integrative phase.

Statistical Analysis(SSB)

A statistically significant lower amount of self absorbed and stereotypic behaviour was found in comparison to baseline freeplay in C1, C2 and C3 after application of Friedman’s ANOVA to the data.

The Wilcoxon signed-ranks test confirms these claims. Other significant differences between treatments included lower level of SSB during sensory integration when compared to adaptive play and audio/visual stimulation in C1 and lower SSB in C2 in comparison to audiovisual stimulation.

SUMMARY

Visual analysis of the data suggested that sensory integrative procedures produced the highest mean scores for vocalisation, enjoyment and on task behaviour for C1, C2 and C3 in comparison to baseline freeplay. In addition, non participatory intermission time, and self absorbed and stereotypic behaviour scores were lowest during sensory integration phases of treatment for all three children.

Statistically, however, the superiority of the sensory integrative procedures was not consistently demonstrated.

Vocalisation scores were only significantly higher during the sensory integration phase for C1 than adaptive play and baseline freeplay.

Enjoyment scores were significantly higher during the sensory integration phase for C1 in comparison to adaptive play and baseline only; and for C2 in comparison to audio/visual stimulation. For C3, sensory integration achieved higher enjoyment scores than all other phases.

C1, C2 and C3′s on task behaviour was significantly higher than baseline freeplay scores, but not in comparison to other interventions.

Sensory integrative procedures produced non participatory intermission time scores that were lower than all other interventions indicating the least passivity occurred during this intervention phase across all children.

Finally, sensory integrative procedures produced significantly less self absorbed and stereotypic behaviour than all other interventions except adaptive play for C2.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study are similar to other studies that have researched the link between sensory integration, vocalisation and language. Many of these studies, however, reportedly did not use sensory integrative procedures correctly (Ottenbacher, 1983; Brody et al, 1977; Magrun, et al, 1981; Delly, 1987; Reilly et al, 1983; Kanter, et al, 1982). Others were able to offer no empirical evidence (Behan, 1979). Both Carlsen (1975) and Kanter et al, (1982) found no significant difference between sensory integration and other types of treatment. This study provides some empirical evidence to support the use of sensory integrative procedures with children who have multiple disabilities. However, there are no significant differences between sensory integrative procedures and other interventions for C3′s vocalisation. C3 had a higher level of vocalisation before intervention was introduced than did C1 and C2. This may be why the effects for C3 were not as great. Brody et al, (1977) reported similar findings whereby a child made better gains as a result of sensory integrative procedures if the child had moderate levels of vocalisation. It would seem therefore, that the use of sensory integrative procedures is an appropriate form of intervention for early production of vocalisations and words. This type of communication is vital for social interactions that form a part of social occupations such as play.

It is reported that too much sensory input or too little can contribute to disorganisation which in turn disrupts occupational performance (Fisher, Murray & Bundy, 1991). Just the right amount of arousal is required for enjoyment. For this reason, it could be hypothesised that if a child derives pleasure from the intervention, then organisation occurring is adaptive (Fisher, Murray & Bundy, 1991). Enjoyment can be interpreted as a type of purposeful interaction with the environment that is an integral part of play. Fun, expressed through enjoyment, is therefore an important product of occupational therapy intervention that assists the child to initiate and maintain social interaction necessary for play occupations.

The positive effect of sensory integrative procedures seen in this study is possibly due to several aspects of the sensory integrative mode of treatment. First, the treatment offered challenge within supported equipment. Second, the therapist was involved as a co-player in all activities and could quickly grade them according to the child’s reactions. Third, while choice is inherent to all interventions that promote occupational performance (Chapparo & Ranka, 1996), with these children, sensory integrative procedures gave the child the greatest amount of control over choice during intervention. These findings are consistent with studies reported by Weeks (1979) and Leveille (1981) who found that sensory integrative procedures promoted enjoyment. In these two studies, however, Weeks (1979) had no control group and Leveille (1981) used descriptive case study methods. This study provides empirical support for the notion that sensory integrative procedures provide immediate enjoyment as part of the play response. This enjoyment, in turn, contributes not only to social interaction, but also to the child’s ability to modulate sensory experiences.

Appropriate balance of excitation and inhibition of sensory stimuli is required for the organisation of attention. Ayres (1972) stated that movement is one of the most powerful organisers of this balance. Movement is said to allow active involvement of the child with the visual and motor experience as opposed to a passive experience such as looking at pictures. It helps in the focussing of attention by integrating touch, movement and vision (Fisher, Murray & Bundy, 1991). That sensory integrative procedures have a beneficial effect on attention has been reported by many authors (Behan, 1979; Leveille, 1981; Scheider et al, 1991; Geniale, 1986; Wilson, 1979). In this study, all children benefited from the immediate effects of sensory integrative procedures on attention. It yielded statistically significant greater effects than baseline freeplay, but no consistent significant differences in comparison to other forms of intervention. From a clinical perspective, however, all the children achieved the greatest mean attention scores during the sensory integrative phase of intervention. Attention to task is necessary for social interaction, for imitating others and for inhibiting inappropriate behaviours. Attention is stimulated readily in a novel environment. This may explain why sensory integrative procedures are more effective than other interventions in gaining attention. In comparison to the other interventions used, sensory integrative procedures included novelty as an integral part of the treatment process. Although the continually changing audio/visual stimulation provided novelty, it resulted in poor attention to task. With these children, this type of stimulation appeared to act more as a distracter, causing an overload of input that could not be actively inhibited by the child.

Overload of excitatory input or underarousal may promote non participatory behaviour. Sensory integrative procedures in this study produced significantly less non participatory behaviour in comparison to all other interventions. This may be due to the co player role of the therapist, or the challenge of the treatment (Fisher, Murray & Bundy, 1991). Active participation was a requirement of the treatment. Other forms of intervention used in this study did not appear to offer the range of activities and supportively stimulating equipment to keep the children consistently actively involved in therapy.

Children with severe disabilities have a limited repertoire of play and movement skills (Nelson, 1984). The movements used by them during the course of everyday activities are stereotypic, rather than varied and purposeful. Purposeful occupational performance requires purposeful social interaction that demands self absorbed behaviours be kept at a minimum (Nelson, 1984). Sensory integrative procedures in this study resulted in significantly lower levels of self absorbed behaviour than any other intervention. Previous studies have also reported sensory integrative procedures to be effective in reducing self absorbed behaviour. One exception to produce consistent positive results was as study by Mason & Iwata, (1990), however, these researchers failed to demonstrate whether purposeful activity or therapist interaction was an integral part of the intervention applied.

Using single subject methodology, this study has demonstrated that occupational therapy interventions employing play occupations are useful for three children with severe multiple disabilities in increasing vocalisation, attention to task, and in decreasing self absorbed and stereotypic behaviour and passivity. When comparing the three interventions, the study demonstrated that the immediate effects of sensory integrative procedures within a play context were superior to other modes of intervention in decreasing self absorbed and stereotypic behaviour and passivity. Sensory integrative procedures also functioned to increase the amount of vocalisation, on task behaviour and enjoyment during play occupations, but with no consistent significant differences from other interventions. While not all changes were statistically significant, the immediate effects of sensory integrative procedures consistently produced the highest mean directions for vocalisations, enjoyment and on-task behaviour. Tentative conclusions that can be drawn from this study suggest that sensory integrative procedures are an effective form of intervention for this population of children to facilitate behaviours required for the occupational role of player.

The focus of this study was on immediate effects of occupational therapy intervention, as opposed to long term effects. Many therapists base long term treatment modes on the initial reactions obtained during short pilot periods of therapy. The assumption is that if a child can achieve observable improvement in a target behaviour in the short term, the child could achieve the same results with more consistency with further intervention of the same mode. This assumption has to be supported by further research into long term outcomes of a variety of interventions. The limitations of this study are recognised. Small sample size restricts generalisability. Further replication studies are required. The scope of play behaviours studied are limited. Increased numbers of behaviours that support the occupational role of player need to be investigated. Considering the variability in some of the results, it is evident that larger clinical trials are needed to identify those children who could be considered optimum candidates for various forms of intervention.

The broader significance of this study lies in its identification of sensory integration as a therapy mode that contributes to the development of the occupational role of player in children with multiple and severe disabilities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the following people to this study: the three children who participated in the study and their families; Jill Hummell DipOT,BA,MA; and the staff of the Institute for Deaf and Blind Children, Norths Rocks.

References

Alice Betteridge School (1988) Information pamphlet on audio vi sual stimulation. Speech Pathology Department, Alice Betteridge School, North Rocks Rd., North Rocks, 2151

Allard, J. (1987) New ways with lighting. Kidderminster: Alexander Patterson School, Unpublished paper.

Anderson, J., Hinoojosa, J., & Strauch, C. (1987) Integrating play in neurodevelopmental treatment. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 41(7), 421-426

Arendt, R., Maclean, W., & Baumeister, A. (1988) Critique of sensory integration therapy and its application in mental retardation. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 92(5), 401-411

Armstrong, J.E., & Rennie, J. (1986) We can use computers too. The setting up of aproject for mentally handicapped residents. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 49(9), 297-300

Ayres, A. J. (1979) Sensory integration and the child. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services

Ayres, A. J. (1972) Sensory integration and learning disorders.. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Blanche, E. J. (1992) Creativity in sensory integrative treatment. Sensory Integration Special Interest Section Newsletter, 15(1), 3-4

Blanksby, D.C. (1992) Visual therapy: a theoretically based intervention program. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, September, 291-294

Bright, T., Bittick, K., & Fleeman, B. (1981) Reduction of self-injurious behaviour using sensory integrative techniques. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 35(3), 167-172

Brody, J. F., Thomas, J.A., Brody, D.M., Kucherway, D.A. (1977) Comparison of sensory integration and operant methods for production of vocalisation in profoundly retarded adults. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 44, 1283-1296

Caplan, F., & Caplan, T. (1974) The power of play. Garden City: Anchor Books

Carlsen, P. N. (1975) Comparison of two occupational therapy approaches for treating the young cerebral palsied child. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 29(5), 267-272

Cermack, S., & Henderson, A. (1990) The efficiency of sensory integrative procedures. Sensory Integration Quarterly, XVIII(1), 1-5

Chapparo, C., Hummell, J., MacMillan, C., & Rumble, D. (1991) Effects of sensory integration on social interaction skills. Proceedings of the 14th Federal Congress of the Australian Association of Occupational Therapists. Adelaide: AAOT

Chapparo, C., & Ranka, J. (1996) The occupational performance model (Australia): Draft Manuscript. School of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Health Sciences, The University of Sydney, East St., Lidcombe. NSW. Australia. 2141. May.

Christiansen, C. (1991) Occupational therapy. Intervention for life performance. In C. Christiansen & C. Baum (Eds.). Occupational therapy: Overcoming human performance deficits. (pp.3-43). Thorofare: Slack Inc.

Clark, F., Mailloux, Z., & Parham, D. (1989) Sensory integration and children with learning disabilities. In P.N.Pratt & A.S.Allen (Eds.). Occupational therapy for children. (2nd Ed.). (pp457-507). St. Louis: The C.V.Mosby Co.

Cummings, F. J. (1989) Children with communicative impairment. In P.N.Pratt & A.S.Allen (Eds.). Occupational therapy for children (2nd ed.). (pp.442-456). St. Louis: C.V.Mosby Co.

Demchak, A. (1990) Response prompting and fading methods: a review. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 94(6) 603-615

Eckerman, C.O., Davis, C.C., & Didow, S.M. (1989) Toddler’s emerging ways of achieving social coordinations with a peer. Child Development. 60, 440-453

Erhardt, R.P. (1987) Sequential levels in the visual-motor development of a child with cerebral palsy. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 41(1), 43-49

Fisher, A., Murray, E., & Bundy, A. (1991) Sensory integration theory and practice. Philadelphia: F.A.Davis Co.

Freeman, P. (1975) Understanding the deaf and blind child. London: Heinemann Health Books.

Gallagher, R.J., & Perkson, G. (1986) Effect of intervention techniques in reducing stereotypic hand gazing in young severely disabled children. (2), 170-177

Geniale, P., Graham, F. & Quee, B. (1986) Occupational therapy at the special school. Lantern Light. November/December, 6-7

Goetz, L, & Gee, K. (1987) Functional vision programming. A model for teaching visual behaviours in natural contexts. In L.Goetz, D.Guess & K.Stremmel-Campbell (Eds.), Innovative program design for individuals with dual sensory impairments (pp. 77-97). Baltimore:Paul Brooks

Hacker, B. (1980) Single subject research strategies in occupational therapy. Part 1. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 34(2), 103-108

Hilke, D.D. (1988) Inant vocalisation and changes in experience. Journal of Child Language. 15, 1-15

Iwasaki, K., & Holm, M.B. (1989) Sensory treatment for the reduction of stereotypic behaviours in persons with severe multiple disabilities. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research. 9(3), 170-183

Josefowicz, A. (1980) Preparing the young handicapped child for school. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 43(7), 230-232

Kanter, R.M., Kanter, B., & Clark, D.L. (1982) Vestibular stimulation effect on language development in mentally retarded children. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 36(1), 36-41

Kazdin, A. E. (1982) Single case research designs: Methods for clinical and applied settings. New York:Oxford University Press.

Kelly, G. (1987) Occupational therapy for speech and language for disordered children: A sensory integrative approach. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 50(4), 128-131

Kimball, J. (1988) The emphasis is on intergration, not sensory. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 92(5), 423-424

Lagrow, S. J., Prochnow-Lagrow, J.E. (1983) Consistent methdological errors observed in single case studies: Suggested guidelines. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, December, 481-488

Lee, C. (1977) The growth and development of children. London:Longman Group Ltd.

Lehrer, A. (1981) An occupational therapy pediatric research project in community integration. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 48(3), 115-119

Leveille, J. (1981) Outline of a sensory integrative approach with a chronic tactile defensive schizophrenic. British Journal of Occupational Therapy.( ). 160-162.

Magrun, W. M., Ottenbacher, K., McCue, S., & Keefe, R. (1981) Effects of vestibular stimulation on the spontaneous use of verbal language in developmentally delayed children. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 35(2), 101-104

Mann, J., Have, T.T., Plunkett, J.W., & Meisels, S.J. (1991) Time sampling: A methodological critique. Child Development, 62, 227-241

Mason, S., & Iwata, B. (1990) Artificial effects of sensory integrative therapy on self-injurious behaviour. Journal of Applied Behaviour Analysis., 23(3), 361-370

Michelman, S. (1974) Play and deficit child. In M. Reilly (Ed.), Play as exploratory learning (pp. 157-207). Beverly Hills: Sage Publications

Nelson, D. (1984) Children with autism and other pervasive disorders of development and behaviour. New Jersey: Slack Publications

Ott, L. (1988) An introduction to statistical methods and data analysis. (3rd Ed.). Boston: PWS-Kent Publishing Co.

Ottenbacher, K. (1991) Research in sensory integration: Empirical perceptions and progress. In A. Fisher, E. Murray & A. Bundy (Eds.). Sensory integration theory and practice. (pp. 385-399) Philadelphia: F.A.Davis Co.

Ottenbacher, K. (1988) Sensory integration: myth, method and imperative. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 92(5), 425-426

Ottenbacher, K. (1986) Evaluating clinical change: Strategies for occupational and physical therapists. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins

Ottenbacher, K. (1983) Developmental implications of clinically applied vestibular stimulation: a review. Physical Therapy. 63(3), 338-342

Ottenbacher, K., & Short, M. (1985) Sensory integration dysfunction in children: a review of theory and treatment. In D. Routh & M. Wolrich (Eds.). Advances in Development and Behaviour; Pediatrics. Vol.6. (pp. 286-329). Greenwich: JAI Press

Parham, L.D. (1992) Strategies for maintaining a playful atmosphere during therapy. (1), 2-3.

Penso, D.E. (1987) Occupational therapy for children with disbilities. London:Croom Helm

Pratt, P.N., & Allen, A.S. (Eds.). (1989) Occupational therapy for children (2nd Ed.). St. Louis:C.V.Mosby Co.

Reilly, C., Nelson, D. L., Bundy, A. G. (1983) Sensoimotor versus fine motor activities in eliciting voclalisation in autistic children. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, 3(4), 199-212

Schneider, B.E., & Marks, H.E. (1989) Changes in preschool children’s IQ scores as a function of positioning. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 43(10), 685-687

Sents, B.E., & Marks, H.E. (1989) Changes in preschool children’s IQ scores as a function of positioning. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 43(10), 685-687

Snow, B. (1989) Children with visual or hearing impairment. In P.N.Pratt & A.S.Allen (Eds.). Occupational therapy for children (2nd Ed.) (pp.535-562). St. Louis: C.B.Mosby Co.

SPSS Inc. (1990) SPSS reference guide. Illinois: SPSS Inc.

Stewart, H.A., Ormond, C., & Seeger, A. (1991) Toy control program evaluation. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45(8), 707-711

Weeks, Z. (1979) Effects of the vestibular system on human development. Part 2. Effects of vestibular stimulation on mentally retarded, emotionally disturbed and learning disabled individuals. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 87(6), 664-666

Wilson, E. B. (1979) Some impressions on the effect of sensory integrative therapy for children with learning disabiilties. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 26(1), 12-20