CONSTRUCT 8: TIME

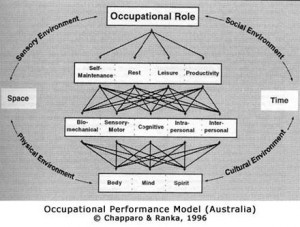

Time is the final construct of the Occupational Performance Model (Australia) and has been defined as a system of relating one successive event to another (Delbridge, 1981, p.1808). Just as with descriptions of the spatial construct outlined previously, time is conceptualised in this model as physical time and felt time. Time is also represented in the model as a gray overlay (Fig. 9).

Physical time is also derived from laws of physics which attempt to explain the temporal aspects of physical changes seen during occupational performance. This is usually expressed in terms of sequential or simultaneously occurring events. For example, at the level of core elements, neuronal processes are described not only in terms of spatial configurations but also in terms of time. At the level of the environment, one representation of physical time is the cycles of the moon and sun.

Felt time is a person’s understanding of time based on the meaning that is attributed to it. As with felt space, felt time involves highly personal abstractions of time that have representation at all levels of the model. It is an experiential abstraction that is being constantly changed and modified by experience. April, 1997, Monograph 1 18

Figure 9: Time and its relationship to other constructs in the Occupational Performance Model.

Together, physical and felt time contribute to occupational performance at any level. Immediate time has representation at the component level, where various biomechanical, sensory- motor and cognitive operations occurring in the here and now contribute to task performance. Immediate timing of interactions between people contributes to appropriateness of specific instances of social interaction. At the level of core elements, time is essential to muscle contraction, neuronal transmission and a spiritual feeling of the ‘right’ time. At the level of the occupational performance areas, immediate timing of subtasks is essential to forming sequential routines. At the occupational role performance level, immediate timing of events serves to link people to social and environmental circumstances, thereby establishing a feeling of being in the ‘right place’ at the ‘right time’.

Broad notions of linear time are derivatives of western society, and establish boundaries for how people in those societies ‘spend time’ throughout the day, week or year. Beyond the broad developmental concepts of time relating birth to death, linear time can be viewed more abstractly as simply the ‘unfolding of time’ and therefore is important to sequencing of occupations, particularly routines and tasks that occur over time and in concert with others in the environment of all people (Peat, 1994).

Cyclical time heralds feelings of ‘knowing’ when events should happen, and occurs with repetition of occupations to the point where they become habitual, thereby grounding us in ‘place’.

The external environment has its own time, that is composed of physical elements as well as the timing of external events to which individual notions of time must be matched. This aspect of time is essential for satisfactory occupational role performance.

As with the concept of felt space, notions of felt time vary from person to person and from one culture to another. In many cultures, time is often modeled in a similar way to a spatial coordinate. A common spatial coordinate that represents time is a ‘day’. In Western cultures, a day is 24 hours. In other cultures, a day is from sun up to sun down. In many cultures, a day, as defined by that culture, is a specific period of time through which much of peoples’ lives are ordered. In these cultures, the pattern of occupational performance is partly organised by this ‘defined’ time span which is conceptualised as linear, circular or spiral. Many occupations are similarly organised on other models of time such as seasons, weather patterns and patterns of the social group. Still other cultures have no formal model of time, although there exists some abstraction of time relative to the period that exists between the beginning and the end of the performance of concrete living tasks, of falling asleep and coming awake again, of the sun coming up and going down and of the repetition of these types of activities and events. Abstractions of time such as synchronising events and actions to coordinate with each other and the regulation of actions relative to speed and some indefinable internal notion of ‘the right time’, are fundamental to the sense of time of all people (Popper, 1981).

Conceptualisations of time presented in this model are constrained by the authors’ western Occupational Performance Model (Australia) 19 cultural understanding of time. Before using this model to explain abstractions of time relative to other cultures, therapists would need to investigate the prevailing abstraction of time within that culture and, if possible, revise its relationship to other constructs within the model.

Time refers to a temporal ordering of physical and other events (Physical Time) as well as a person’s understanding of time based on the meaning attributed to it (Felt Time).

An extended concept of space and time, in this model, is the notion of ‘place’. Place is a particular portion of space of definite or indefinite extent. Therefore, place refers to space as it exists in connection with time (Delbridge, 1981, p.1320). Authors such as Rowles (1991) and Seamon and Nordin (1981) have theorised about the nature of being “in place”. They describe this as an everyday life phenomenon that occurs through a process of immersion within a spatiotemporal setting. This setting can be in the present or the remembered past or the imagined future, thereby setting the horizon for occupational performance in everyday life.

Acknowledgment of space and time as expressed by being ‘in place’ affirm that there are dimensions to human occupational performance that are not productivity driven. These dimensions arise through the identityreinforcing potential of non-instrumental aspects of being ‘in place’ such as reminiscence (remembering life histories), reflection (reviewing thoughts and actions) and immersion in spatially or temporally displaced environments (daydreaming and imagining).

Similarly, when considering spatiotemporal aspects of the external environment, it becomes much more than the physical or sociocultural setting for performance. The phenomenological perspective of felt time and space embraces the sensory, physical, social, cultural and historical dimensions of an environment of lived experience. Therefore, the environment as a spatiotemporal world not only includes the person’s current setting, but also has a space-time depth that is uniquely experienced within the framework of a personal history.

Analysis of Occupational Performance: Space & Time

As described, elements of space and time are embedded in occupational performance at every level of the model. The implication for analysis of occupational performance is to:

- be vigilant in considering both space and time dimensions of occupational performance.

SUMMARY

Current notions of occupational performance are being developed worldwide both as a guideline for practice (Canadian Association of Occupational Therapy, 1991) and as a means of developing a common professional language (American Occupational Therapy Association, Inc. 1989). This article describes the Australian contribution to this endeavour which extends existing conceptualisations through the development of a model of occupational performance that explains the structure of human occupational performance. The Occupational Performance Model (Australia) (Appendix 1) is structured around eight constructs, occupational performance, occupational performance roles, occupational performance areas, components of occupational performance, core elements of occupational performance, environment, space and time.

This article describes the beginning stage of theorising about occupational performance by defining construct terminology and suggesting how these constructs are related. Modifications of constructs and terminology will occur as the model is subjected to further research and development, and as a result of field testing in practice situations. April, 1997, Monograph 1 20