CONSTRUCT 7: SPACE

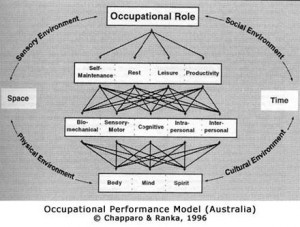

Space is defined as an expanse which extends in all directions, in which all material objects or forms are located. The Occupational Performance Model (Australia) extends these notions of surrounding space to incorporate both internal and external components (Fig. 8). External space surrounds people as objects in space, but people themselves contain internal space that is filled with objects in the form of body structures. The concept of internal space April, 1997, Monograph 1 16 corresponds with contemporary notions of human function. Theorists describe a human three dimensional spatial coordinate system that functions to understand external space and an internal spatial system that identifies body parts as they relate to each other and external space (Gilfoyle, Grady & Moore, 1981; Stelmach, 1982).

Human understanding of internal and external space is conceptualised in this model as physical space and felt space. Physical space is derived from the technical construct of space as viewed by physics. Both objects and space are composed of physical matter; therefore, the law of physics governs notions of physical space. From this is derived, in part, our understanding about body structures, body systems, objects with which people interact and the wider physical world within which people exist and function.

Of more importance to occupational performance is the notion of felt space. Although people are surrounded by physical space, the meaning they attribute to it, the way they use it and their interactions within it, are largely determined by how they interpret it. This interpretation is referred to in the Occupational Performance Model (Australia) as felt space. Felt space is a personal, dynamic view of physical space as experienced by each individual. The meaning that is attributed to physical space during occupational performance has representation within all the constructs previously described and is therefore represented by a shaded overlay (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Space and its relationship to other constructs in the Occupational Performance Model

For example, external objects and space impinge on people’s various sensory receptors at the level of core elements of occupational performance. This information results in an understanding of the form and space elements of the environment through a complicated process of interpretation involving the biomechanical, sensory-motor, cognitive and affective components. Similarly, people become aware of internal body processes through the interpretation of information that is processed at the core element and component level of occupational performance. For example, the active movement that occurs during performance of an occupational task results in biomechanical Occupational Performance Model (Australia) 17 changes in the spatial relationship between body segments. Processing of the complex sensory information involved in movement through space and interactions with objects in space results in cognitive understanding of the body in space and of its relationship with objects in space. Part of the meaning that is attributed to space and objects within space contains an affective or emotional component that contributes to feelings about oneself as an object in space, about the type of relationship that exists between oneself and space, and about the relationship between oneself and other objects in space. Biomechanical, cognitive, sensory-motor, interpersonal and intrapersonal perspectives of form and space are integrated to generate a highly individualised account of form and space components of every step of every occupational task that is perceived, remembered, planned or carried out in life.

At the level of performance of routines, tasks and subtasks felt space provides people with a means of constructing, organising and schematising experiences for planning or performing occupational tasks. Specifically, for occupational performance, it provides people with a way to conceptualise routines, tasks and subtasks in terms of their form and structure. People understand and explain to others what needs to be done by describing the final form of the task, by consciously or unconsciously segmenting performance into partially completed forms that finally become a completed task, and by describing the relationship of external objects and body parts during each segmented part of the performance.

At the level of occupational performance roles, spatial understanding of occupational routines and tasks, linked with time, goes further than merely providing people with a means of constructing a picture of the spatial world within which they perform occupational tasks. At this level, spatial concepts of regular and intermittent routines culminate in a routine that is given meaning in terms of structure and form. For example, in many cultures, descriptions of the role of a worker is to a large extent place and space dependent. People describe their work role(s) relative to what they do (the final form), the people or tools they work with (objects) and where they work (position in space). Children who describe their play role(s) often do so according to what they play with (objects), the ‘rules’ of the game (the relationship of objects) and later, who they play with (people as objects). Felt space contributes to each person’s ability to construct his/her own particular world, characterise events within that world and most importantly, engage in the social phenomenon of sharing his/her understanding of that world within a culture (Bruner, 1990).

Incorporating notions of both physical space and felt space, this model uses the term, space as follows.

Space refers to compositions of physical matter (Physical Space) as well as a person’s view of experience of space (Felt Space).