TheOccupational PerformanceModel (Australia): Applicationto group interventionfor childrenwith handwritingproblems

Traci-Anne Goyen, Sharon Doyle,

Christine Chapparo

Traci-AnneGoyen, BAppSc(OT) is an occupational therapist at Westmead Hospital’sGrowth and Development Clinic and operates her own private practice.

SharonDoyle, BAppSc(OT) is an occupational therapist at the New Children’sHospital, Westmead, NSW. Australia

ChristineChapparo, MA,DipOT,OTR,FAOTA, is a senior lecture in the School ofOccupational Therapy, The University of Health Sciences and aclinical consultant to Westmead Hospital, Department of OccupationalTherapy

In 1995, the Occupational Therapy Department at Westmead Hospital had an extensive waiting list for children with Perceptual Motor Dysfunction. Perceptual Motor Dysfunction is a term used to describe preschool and school-aged children of normal intelligence, with no identifiable neurological pathology, who may have difficulties in fine motor skills, general coordination, handwriting, perception and learning (Wallen & Walker, 1995).

Strategies were implemented to reduce the waiting time for intervention. One such strategy, group intervention, was trialled for children with handwriting difficulties as an alternate approach to traditional individual intervention. Handwriting was chosen as the focus for a group intervention because handwriting difficulty was one of the most frequent reasons that school-aged children were being referred to occupational therapy.

Services that were known to offer group intervention for children with handwriting difficulties were contacted. Suggestions and descriptions were sought regarding the best way to approach this type of intervention. A number of these services had established therapy groups based on ‘preventative intervention’, in which they addressed instruction in ‘good’ handwriting practices, such as preferred writing postures and pencil grasps, to improve handwriting performance. Others were more ‘prescriptive’, using a programmed sequence of activities that addressed skills associated with handwriting function, such as visual-motor and copying tasks.

In our view, these programs failed to address the assessment and intervention of handwriting in a wholistic manner and they appeared to lack a clear framework within which to examine the total routine of handwriting.

A flexible approach to group intervention for handwriting was developed by the authors to meet the individual needs of children within a group context. While a flexible and wholistic approach to intervention for handwriting was preferred, it was clear that this could not be achieved effectively without an overall framework to guide aspects of group intervention.

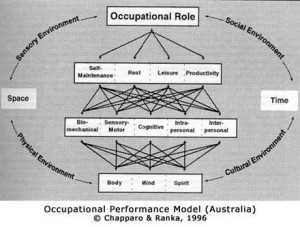

To allow for individual skills, abilities and attitudes of children to be addressed within the context of a group programme, a theoretical model was sought within which individual goals could be made to guide intervention. The Occupational Performance Model (Australia) (Chapparo & Ranka, 1996) was used to develop a framework for the group program. This particular model was employed as it was viewed as allowing therapists to:

1) analyse and explain the impact of poor performance in handwriting on the child’s total occupational context;

2) identify and address both global and specific areas of handwriting difficulty for each child within a group context; and

3) provide therapists with a clear explanation of the role of the occupational therapy with children who have handwriting problems.

The purpose of this paper is to illustrate how the Occupational Performance Model (Australia) (Chapparo & Ranka, 1996), can be used to direct assessment and a group intervention programme for children who have handwriting difficulties.

ANALYSISOF HANDWRITING USING OCCUPATIONAL PERFORMANCE

CONSTRUCTS

Problems in handwriting are characterised by a number of different features. Often, therapists concentrate onanalysis of the most common characteristic, poor legibility and speed (Cermack, 1991; Wallen, Bonney & Lennox, 1996). Alternatively, others focus on underlying component function without linking the disorder to handwriting difficulties (Doyle & Goyen, 1997). It is unusual, however, that difficulty with handwriting is not associated with other aspects of occupational performance. Handwriting is performed within a personal and environmental context. It is embedded in school and home occupational roles where there is demand for a particular level of performance. Poor handwriting may be a graphic symptom of a learning disability, and therefore linked to associated difficulties with perception, motor planning, motor memorymotor sequencing and language (Benbow, 1995; Cermack, 1991; Stott, Moyes & Henderson, 1985; Levine, 1985). Inadequate strength of the finger muscles or an imbalance between flexor and extensor muscle strength may cause poor pencil grasp and handwriting (Benbow, 1990). Alternatively, behavioural disorders may impact on handwriting performance (Wallen & Doyle, 1995). Long term difficulty with handwriting impacts negatively on self esteem and self efficacy in children of all ages (Benbow, 1995).

Once it has been determined that a child has a problem with handwriting, it is critical to successful intervention that the reasons for the existing problem, as well as the impact of the problem on other occupations are fully analysed. Using the constructs within the Occupational Performance Model (Australia), (Chapparo & Ranka, 1996), guidelines for the depth and scope of handwriting assessment as well as intervention within the group context were developed. This particular occupational performance model is based on a top-down approach (Chapparo & Ranka, 1993). Its constructs and structure emphasise the child’s performance in terms of roles and complex tasks (Chapparo & Ranka, 1996). Relative to this model, the focus of handwriting intervention is therefore linked to the promotion of occupational role mastery. Component assessment and intervention occurs only when occupational need is identified at role and task levels. To define what constitutes mastery of handwriting for a specific child, the therapists must have knowledge of the child’s educational and play environment. The demands of these environments will contribute to the child’s required role expectations.

OccupationalRoles

‘Student’ and ‘player’ roles were identified as the primary occupational roles for school-aged children which could be affected by handwriting difficulties. The ‘student’ spends the majority of the day involved in writing tasks at school (McHale, 1987), and as a ‘player’ the child may choose to engage in a variety of games and activities, many of which may involve writing.

Handwriting of group members is therefore analysed in relation to the occupational role demands of performance. As outlined in the Occupational Performance Model (Australia), (Chapparo & Ranka, 1996), occupational roles have three dimensions: one is personal (knowing what has to be done); one is environmental (what outside expectations exist of performance) and role satisfaction (feelings of satisfaction with role performance). Applying these concepts to handwriting analysis, each child’s personal idea of how he or she wants to use handwriting to express ideas is sought. Similarly, the classroom context has implicit and often explicit demands for the level of performance expected from the student group. Last, children within the group are given opportunities to express their satisfaction with their levels of overall performance (Doyle & Goyen, 1997). Individual handwriting performance is therefore analysed against this real world context using information about perceived, actual and expected levels of handwriting performance from the child, parents and teachers.

Handwriting intervention goals, as they relate to performance of chosen and needed occupational roles, became one of the first steps in the process that guided programme development.

OccupationalPerformance Areas

Within the roles of ‘student’ and ‘player’, the ability to write was considered relative to its place as a routine or task in the ‘productivity’ and ‘leisure’ occupational performance areas.

Leisure routines and tasks

Children frequently engage in writing routines as part of their leisure activities. This may include tasks such as writing letters to penpals or friends, writing stories, and ‘fun’ writing games (such as crosswords, find-a-words, hangman).

Productivity routines and tasks

At school the student is expected to participate in two types of handwriting routines, depending on the age of the child. First, in the early school years, up to about 3rd grade, children spend time in performance of formal handwriting routines that target adequate development of a specific style. Second, around the 4th grade, there is a marked increase in academic demand for written output that emphasises writing reports, stories and projects, and demonstration of knowledge (Levine, Oberkland & Meltzer, 1981).

Tasks that support these routines involve dimensions of the ability to structure handwriting and timing of performance (Chapparo & Ranka, 1996), and include presentation of work in a neat, orderly and timely fashion. In addition, manipulative tasks incorporating multiple tools, such as using a ruler, eraser and compass become integrated into complicated handwriting tasks that are required to complete work. For the student the ability to write legibly and at an appropriate speed is essential for success at school. Furthermore, the legibility of a student’s handwriting can be influenced by a number of factors, including their posture when writing, grasp of the writing implement, organisation of work on the page, and the formation and spacing of letters.

Although there are many handwriting assessments that contribute to information about handwriting difficulties at this level of performance (Doyle & Goyen, 1997), we have found that these should be supported by two additional forms of analysis.

1) Task analysis of routines, tasks and subtasks to identify specific errors or strengths in performance.

Analysisof handwriting routines involves analysis of several critical routines that are required for the child’s successful role performance as student or player. For example, the routine required for writing a short story involves creating a story image in the mind, converting it to words, converting the words to written words, maintaining legibility of writing mode and memorising what is to be written. Often, we see that children are able to write when they can fully concentrate on the mechanical aspects of writing, but not when they have to attend to the information that is in their mind. Similarly, the routine of copying information from a chalkboard requires the child to adaptively put together the performance of several handwriting tasks such as reading the board, remembering what is read, writing the words, finding the next place on the board, and continuing the routine until its close. The added demands of structure and time that are imposed on routines of handwriting are an important feature of any handwriting assessment and intervention programme, as routines often form the link between discrete tasks and role performance.

Specifictask and subtask analysis can further describe the observed errors in handwriting routines. This involves a more indepth analysis of specific steps in handwriting. For example, in one child, the routine of copying from the board may be compromised by difficulty with the specific subtask of visual relocation of words on the board. The key to initial intervention in this case therefore, will not be to practice handwriting, but to practice visually locating words to be written. Similarly, another child may have difficulty with the timing of the same routine due to poor pencil grip. For this child, intervention in the first instance will be directed towards reordering pencil grip. Ultimately, for both these children, the step in the task that is problematic will need to be practiced within the

context of the whole writing routine to ensure

carry through in the classroom (Snell, 1987).

2) There is support in the literature for handwriting analysis to contain a measure of the teacher’s assessment of the child’s handwriting (Cermack, 1991). The teacher, in a classroom full of children has the opportunity to view the child’s performance against other children who are performing the same tasks and routines. In addition, the teacher has the opportunity to look at multiple samples of the child’s work, produced under various personal and environmental conditions. Teachers develop a picture of the level at which the child is able to sustain handwriting routine performance and which environmental and personal elements impact most directly on its quality.

Similarly, it is important to consider information about the child’s handwriting from the parent’s perspective. For example, many parents can identify difficulties with children completing homework, or experiencing pain and aversion during writing which is not evident in the classroom.

Componentcontributions to handwriting

The child’s ability to perform writing routines and tasks at school and for leisure may be compromised by underlying components, including biomechanical, sensory-motor, interpersonal, intrapersonal or cognitive operations (Benbow, 1995; Carr, 1989; Cook, 1991; Dunn & Campbell, 1991; Powell, 1994).

Formal and informal analysis of component function provides information that can assist in clarifying the nature of the handwriting problem.

Assessment of strength and muscle tone provides information which may explain the presence of poor pencil grip, endurance and fatigue during writing tasks and routines. In this instance, part of an intervention programme would need to address increasing hand strength and endurance to support writing (Benbow, 1995).

Sensory motor processing using various standardised measures (Ayres, 1989; Bruininks, 1978; Stott, Moyes & Henderson, 1984; Beery, 1989; Miller, 1988; Royeen, 1990) or informal observations can give information about the presence of visual, kinaesthetic or other sensory

processing disturbances associated with poor handwriting. For example, some children who have poor handwriting have inadequate somatosensory perception (Benbow, 1995; Levine, 1985; Cermack, 1991). This may be manifested in tests of finger identification, or knowing the precise position of hands and fingers. Children who do not adequately process somatosensory information may try to compensate for inadequate sensory feedback by using undesirable pencil grips. These are usually characterised by increased pressure and stabilisation of the distal joints of the index finger and thumb. For longer writing routines, this may result in fatigue. Similarly, a general problem with motor planning may result in poor development of automatic movements that are needed for skilled and quick writing. The child must think about the mechanics of writing rather than the content of writing, thereby limiting the length of academic work produced.

For some children, specific perceptual and cognitive deficits may be the foundation for errors in writing tasks. For example, Levine (1985) suggested that there was a need to differentiate component physical problems with writing from component cognitive problems, specifically language operations such as word finding and sentence formation. For example, the child whose handwriting problems are mostly centered around letter reversals, is probably demonstrating primarily language deficits, rather than handwriting deficits of the motor type.

The extent to which children are able to experience positive intrapersonal elements of task performance contributes to general self esteem and confidence. Emotional stability, mood and motivation are all intrapersonal dimensions of a child that can impact on the consistency of handwriting performance.

Externalenvironment

Physical and sensory environments contribute to how well the child is able to structure and time handwriting routines. Sociocultural dimensions of the external environment play a major part in determining the level of mastery of handwriting performance (Orr & Schkade, 1996), as described previously. Authors have indicated that the environmental demands of the school setting, for example, can contribute to the identification of intervention needs (Brollier,

Shepherd & Markley, 1994; Griswold, 1994; Haley, et al, 1992). In developing a programme for children with identified handwriting problems, therapists are often responding to the environmental demands of the classroom, or family expectations, rather than the individual concerns of the child. Any intervention model that guides programmes for effective handwriting, must consider the environmental influence on performance. The Occupational Performance Model (Australia) (Chapparo & Ranka, 1996), is one model of practice that appears to consider the prominent place of the environment to occupational performance.

Timeand Space

Timing of role, routine and component functions contribute to the efficacy of handwriting performance and the space in which the writing task occurs can influence a child’s performance at any level of the model. Time, in the form of developmental expectations of handwriting at different ages is a major consideration in assessment and intervention.

Below, is a summary breakdown of how handwriting performance with its various elements are viewed in relation to constructs in the Occupational Performance Model (Australia), (Chapparo & Ranka, 1996). The constructs depict occupational performance areas that can be targeted for:

1)goal setting

2)intervention.

3)programme outcome measures

OCCUPATIONALROLES THAT REQUIRE HANDWRITING

Student

Player

OCCUPATIONALPERFORMANCE AREAS THAT INCLUDE HANDWRITING

Productivity

Examplesof Handwriting Routines

near and far point copying

dictation

projects

spelling lists

creative writing

exams

worksheets

Examplesof tasks and subtasks

1) legibility (structure) of handwriting

*spacing of letters and words

*formation of letters (including size, case and slope)

*organisation of written material (including alignment)

*grasp of writing implement (including type and consistency of grasp)

*posture when writing

*pencil and paper management (including positioning, manipulation of pencil in hand, stabilising paper)

*writing pressure)

2) speed (timing) of handwriting

*fluency

3)Manipulativetasks related to handwriting

*use of ruler

*eraser

*folding paper

Leisure

Examples of handwriting Routines

*correspondence

*writing for games

*poetry and creative writing

COMPONENTSOF OCCUPATIONAL PERFORMANCE

Biomechanical

Range of Movement

Muscle strength

Grasp

Biomechanical development of the hand and thumb

Body posture

Stabilisation of joints

Sensory-Motor

Postural control and stability

Regulation of muscle tone

Bilateral coordination

Gross motor coordination

Fine motor coordination and control

In-hand manipulation

Visual-motor integration and control

Awareness of body position and movement in space

Planning and organising movement sequences

Sensation including the presence or absence of pain and discomfort

Cognitive

Attention and concentration

Memory, recall, retention and sequencing of ideas

Thinking, perceiving, recognising and knowing

Problem solving, decision making, planning and judgement

Visual perception

Language skills

Thinking and doing simultaneously

Formulating and translating ideas

Intrapersonal

Self esteem and confidence

Intrinsic motivation

Perseverance with difficult tasks

Emotional stability, mood and affect

Self control (controlling anxiety levels and impulsivity)

Interpersonal

Group participation skills including cooperation, turn taking, sharing, awareness of personal space and boundaries, empathy, verbal and non-verbal communication

COREELEMENTS OF OCCUPATIONAL PERFORMANCE

TheBody, Mind, Spirit Unit

General well being

Intrinsic motivation

Appropriate muscle tension

Pain-free

Absence of muscle and soft tissue damage

Absence of neuromotor disorder

EXTERNALENVIRONMENT

Social

Individual/group/classroom/home environment and expectations

Writing styles, implements and expectations of peers

Teaching style and educational milieu

Sensory

Amount of light, noise, heat in environment

Colours, textures involved (eg. colour of chalk on blackboard)

Writing surfaces

Appropriate sensory cues within the environment to assist writing

Physical

Ergonomic considerations (eg. seat height, room set up, desk position in class)

Physical proximity to other students

Writing and copying surface (eg. near/far point copying, vertical or horizontal writing surface)

Variety of writing positions

Cultural

Use of modified writing implements at home/school

Multicultural mix in classroom

Individual/family cultural background and expectations

Space

Physical and felt space as positive or negative aspects of handwriting

Time

Past experiences of hand writing

Time of day of writing performance

USINGOCCUPATIONAL PERFORMANCE CONSTRUCTS TO PLOT A HANDWRITING PROFILE FOREACH CHILD IN THE GROUP

Once a child’s handwriting abilities are assessed,

the same constructs within the Occupational Performance Model (Australia), (Chapparo & Ranka, 1996) can be used to construct a complete individual profile for each child’s handwriting, demonstrating strengths and weaknesses of performance. From this information, individual goals are formulated and intervention strategies selected and tailored to meet the individual needs of group members.

INTERVENTION

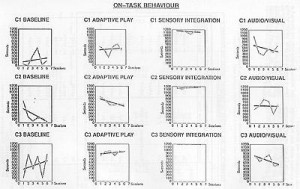

When planning intervention, the model was used in two ways. First, the occupational performance profile for each child was used to determine the level of handwriting intervention needed at the routine, task and component level. Second, the identified areas of need were examined to select appropriate mode and level of intervention. In one group, children could be:

1)working to refine handwriting routines

2)working on specific tasks and subtasks of handwriting that need massed practice

3)working on the component skills or underlying abilities which may have been identified as major contributing factors to poor handwriting.

The art of therapy in a group context in this situation is to construct the task so that all members are working on the same group goal, but at different levels. Sharing, support and mastery can be encouraged as group norms, rather than competition, thereby facilitating confidence and social interaction in a ‘safe’ learning environment.

There is no one intervention mode to which the Occupational Performance Model (Australia) is linked. Two general directions for intervention are found in the structure and underlying assumptions of this model. First, that intervention be occupation centered and linked to an identified occupational need. Second, that the intervention mode chosen by individual therapists suit the level of identified difficulty within the model.

Congruent with this view, there are multiple interventions that are incorporated into this program. First, the program was centered on

handwriting occupations as they related to the identified occupational role need of children referred.

Second, intervention modes chosen matched the identified areas of occupational need within the model. For example, problems with handwriting routines prompt therapists to use systematic instruction that target sequencing and timing of the whole task through prompts and practice of handwriting projects. Often children engage in this level towards the end of treatment. One example of a routine is completion of a group newspaper project.

Specific difficulty with steps of the routine are treated with massed practice of the specific step until mastery is achieved, followed by practice of handwriting routines. For example, children practice graphic patterns with and without lines of decreasing size, followed by letters, finally leading to a motivating writing task. Each session is concluded with a ‘fun’ writing task.

Specific difficulties in the component areas prompt therapists to choose interventions that match the component disorder identified. For example, visual matching and visual memory tasks are used where problems processing visual information are identified; proprioceptive, kinaesthetic and tactile modes of intervention are used where processing in that aspect of sensory motor component function is poor; specific strengthening or orthotic procedures are incorporated into the program when children are identified as having particular difficulties with the biomechanics of writing; general sensory motor procedures are used where children have identified difficulties with body posture and tone when writing. All these component interventions, however, are finally related to the overall intervention goal: improved handwriting.

Profiles of two children are presented in this paper to illustrate how the constructs outlined above have been applied. Due to space available in this article, these case studies focus on assessment and goal setting only. For further information about specific interventions that have been used in the group setting, see Doyle & Goyen, 1996.

CASESTUDY 1 : CHRISTOPHER

Christopher (9 years) was referred to

occupational therapy by the Learning Difficulties Clinic at Westmead Hospital because of presenting concerns with writing at school. Poor writing performance affected his ability to perform effectively as a ‘student’. The performance area which seemed to be primarily affected was his productivity at school. Christopher had difficulty performing and completing writing tasks at school and home, due to fatigue, pain and discomfort in his hand and wrist. His posture during writing was flexedand he made frequent changes with his pencil grip throughout the task. In addition, Christopher had problems manipulating a ruler for writing tasks.

On examination of the underlying performance components which may have contributed to his performance, Christopher was found to have problems with the following biomechanical aspects of writing. He wrote with a flexed wrist which reduced the flow of his movement across the writing surface and contributed to pain when writing.

There was a cognitive component to his difficulty involving higher level language/cognitive skills such as abstract reasoning and inferential thinking abilities. These had been previously identified by the speech pathologist and neuropsychologist from the Learning Disabilities Clinic. Intrapersonal component difficulties that were noted by Christopher, his parents and his teacher, were his lack of confidence and motivation to perform writing tasks in all environments. Assessment revealed that there were no contributing sensory motor or interpersonal difficulties.Environmental considerations included his classroom, which was a grade 3/5 composite class, and that his parents were regularly involved with his homework.

CHRISTOPHER’SPROFILE

OccupationalRoles:student

OccupationalPerformance Areas:

Productivity

*performing and completing writing routines and tasks at school and home, due to fatigue, presence of pain and discomfort

*manipulating ruler for writing tasks

*frequent changes in pencil grip

*poor posture during writing

Componentsof Occupational Performance

Biomechanical:flexed wrist causing pain and reducing flow of movement

Cognitive:high level language/cognitive problems such as abstract reasoning and inferential thinking skills

Intrapersonal:reduced confidence in writing ability

not motivated to perform written

homework tasks

CoreElements

*increased muscle tension in arm

*difficulty relaxing if experiencing pain when writing

Considerationsof Environment/Space/Time:

*composite class 3 and 5

*parents involved in homework regularly

Aims/ Goals of Intervention

PerformanceArea Aims / Goals:

Productivity:

1. To perform and complete handwriting activities at home and at school (including dictation and completing projects) without fatigue or presence of pain and discomfort.

2. To manipulate a ruler so Christopher can rule a line adequately for writing tasks

ComponentGoals:

1. To reduce pain and writing pressure by encouraging more functional (neutral) wrist position during writing

2. To reduce fatigue when writing over a longer

period of time (1/2 page) by improving fluidity and control of movement across the page

3. For Christopher to maintain a more functional posture during writing

4. For Christopher to be motivated to participate in written homework tasks, as indicated by report and performance.

5. To improve confidence in handwriting ability, as indicated by rating scales

Intervention for Christopher was developed within a group structure to meet these goals.

KATE’SPROFILE

Occupational therapy was recommended for Kate (8 years) by her school counsellor due to difficulties with writing at school. This affected her ability to perform effectively as a ‘student’. In addition, her problems with writing also limited her ability and enjoyment when ‘playing’ with others. Her difficulty with handwriting was mirrored in her poor use of tools to complete self care skills. Two performance areas appeared to be primarily affected, including her self maintenance skills and productivity at school. In respect of her self maintenance skills, Kate had difficulty managing eating utensils, and turning taps and knobs carefully.

At school, her handwriting was below average compared to her peers and she experienced pain in her thumb when writing faster. School based fine motor tasks, such as cutting, folding, colouring and using rulers was also problematic.

Examination of the underlying components which affected her performance, Kate was found to have problems with the biomechanical aspects of writing, mainly her fixed, static grip on the pencil with restricted finger movement. Her sensory motor skills, particularly in relation to fine motor tasks were found to be below age expectations. Specific problems were noted with her in-hand manipulation skills and visual motor control, including inaccuracies in completing mazes, copying patterns and with cutting tasks.

KATE

OccupationalRoles:

student

player

self maintainer

OccupationalPerformance Areas:

Productivity

*legibility of writing is below class average

*experiences pain when writing faster

*difficulty with school based fine motor tasks (cutting, folding, colouring, rulers)

SelfMaintenance

*managing eating utensils

*turning taps and knobs carefully

Componentsof Occupational Performance

Biomechanical:

*fixed static grip on pencil restricting finger movement

SensoryMotor:

*below average fine motor coordination (including in-hand manipulation and visual motor control)

InterventionAims / Goals

PerformanceArea Aims / Goals:

Productivity:

1.To reinforce graphic movement patterns during a fun writing activity

2.To improve legibility when required to write faster, as indicated by rating scales

3.To reduce pain when required to write faster for 1 paragraph, as indicated by child report

ComponentGoals:

1.To maintain a functional pencil grip

whilst writing on a vertical surface, to allow controlled and fluent pencil movements for one sentence

2.To perform in-hand manipulation tasks, that will support handwriting and other tool use within the classroom, such as: stabilising 3 beads in the palm while placing beads on thread

Kate and her parents were given the opportunity to address specific self maintenance difficulties at the conclusion of the handwriting group program.

SUMMARY

This paper has illustrated how the Occupational Performance Model (Australia) can be used to structure the assessment and content of intervention for handwriting difficulties. Specifically, the article outlines how the model can be used to determine:

1)the scope required for adequate assessment of handwriting occupations

2)how handwriting can be analysed relative to different levels of occupational performance, including, role performance; routine performance; task and subtask performance; and component performance within environmental constraints.

3)individual handwriting profiles for each child, outlining areas of strengths and weaknesses.

4) goals for intervention

5)intervention options for individual and group intervention

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of colleagues at Westmead Hospital during the development and initiation of this programme.

References

Ayres, A.J. (1989). Sensory integration and praxis tests. Los

Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Benbow, M. (1990).Loops and other groups: A kinaesthetic

writingsystem. Tuscon AZ: Therapy Skill Builders.

Benbow, M. (1995). Principles and practices of teaching

handwriting. In A. Henderson & C. Pehoski (Eds.). Hand function in thechild. (pp. 255-281). St. Louis MO: Mosby

Beery, E. (1989). The developmental test of visual motor

integration.(3rd ed.). Cleveland: Ohio

Brollier, C., Shepherd, J. & Markley, K.F. (1994). Transition

from school to community living. American Journal of OccupationalTherapy, 48, 346-353

Bruininks, R.H. (1978). Bruininks-Oserestky test of motor

proficiencyCircle Pines. MN: American Guidance Service

Carr, S.H. (1989). Louisiana’s criteria of eligibility for

occupational therapy services in public school systems. American Journal ofOccupational Therapy, 48, 503-506

Cermack, S. (1991). Fine motor functions and handwriting. In

A. Fisher, E. Murray & A.Bundy, (Eds.), Sensory integrationtheory and practice. (pp. 166-170) Philadelphia: F.A.Davis

Cook, D.G. (1991). The assessment process. In W. Dunn (Ed.).

Pediatricoccupational therapy: Facilitating effective service provision (pp. 35-47). Thorofare: Slack

Doyle, S., & Goyen, T-A. (1997). Measuring the difference:

evaluatingchange for children with handwriting difficulties. OT Australia. 19th National Conference. Perth. WA. May.

Doyle, S., & Goyen, T-A. (1996). Group intervention for

childrenwith handwriting difficulties.. Allied Health Day. The New Children’s Hospital, Westmead, NSW. August. (Available from the authors).

Dunn, W., & Campbell, P. (1991). Designing pedicatric service

provision. In W. Dunn (Ed.). Pediatric occupational therapy: Facilitatingeffective service provision (pp139-160). Thorofare: Slack.

Griswold, L.A. (1994). Ethnographic analysis: A study of

classroom environments. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 48,397-402

Haley, S.M., Coster, W.J., Ludlow, L.H., Haltiwanger, J.T., &

Andellos, P.J. (1992). Pediatric evaluation of disability inventory (PEDI). Boston: New England Medical Centre Hospitals

Levine, M.D., Oberklaid, F., & Meltzer, L. (1981). Developmental output failure: A study of low productivity in school aged children.Pediatrics, 67, 18-25

McHale, K. (1987). Integrating children with fine motor

difficulties into regular classrooms: An approach to identifying and solving problems. Unpublished master’s thesis. Rhode Island College, Providence, RI. In A. Fisher, E. Murray, & A Bundy, (1991) Sensory integration theory and practice. (p.166) Philadelphia: F.A. Davis

Orr, C., & Schkade, J. (1996). The impact of the classroom

environment on defining function in school-based practice. American Journal ofOccupational Therapy, 51, 64-69

Powell, N.J. (1994). Content for educational programs in school

based occupational therapy from a practice perspective. American Journalof Occupational Therapy, 48, 130-137

Miller, L. (1988). Miller assessment for preschoolers. San

Antonio: The Psychological Corporation

Royeen, C.B., & Fortune, J.C. (1990). TIE:Touch inventory for

school aged children. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 44, 155-160

Snell, M. (1987). Systematic instruction of persons with severe

disability. (3rd ed.). Columbue: Merrill

Stott, D.H., Moyes, F.A., & Henderson, S.E. (1984). The test of

motorimpairment (Henderson rev.) San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation

Wallen, M., Bonney, M., & Lennox, L. (1996).The handwriting speedtest. Adelaide: Helios.

Wallen, M., & Walker, R. (1995). Occupational therapy practice with children with perceptual motor dysfunction: Findings of a literature review and survey. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal,42(1), 15-25