Judy Ranka, Christine Chapparo

Lead paper presented at the 11th International Congress of the World Federation of Occupational Therapists, London (1994, April), and in modified form at the 1st Asia-Pacific Occupational Therapy Congress, Kuala Lumpur (1995, September)

Judy Ranka is a Lecturer in the School of Occupational Therapy, The University of Sydney

Christine Chapparo is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Occupational Therapy, The University of Sydney

PUBLISHED ABSTRACT:

The four year Bachelor of Applied Science degree in occupational therapy [BAppSc(OT)], at The University of Sydney, Australia graduates up to 150 students annually. This curriculum evolved over ten years from one based on a medical model emphasising diagnosis and disease to one founded on the philosophy, assumptions and principles of occupational therapy. This model expands on current concepts of occupational performance and is represented by an interactive structure of seven primary constructs: occupational roles, performance areas, performance components, performance environment, core elements of body/mind/spirit, space and time. By integrating the seven construct categories with principles of curriculum design the authors demonstrate that occupational performance can be employed as an educational model for professional preparation. This represents the first educational model generated from within the profession which is based on a view of occupational therapy practice and has been successfully implemented. One pivotal innovation of this curriculum model is to discard the notion of ‘student’ therapist and focus on professional preparation required to assume the occupational role of ‘therapist’. Learning experiences are designed to actively facilitate professional roles required for practice including those of practitioner, inquirer, teacher/learner, advocate and manager. This paper describes a theoretical base for this curriculum and outlines how the six construct categories form a structure for undergraduate education in occupational therapy.

PAPER PRESENTED:

Introduction:

Throughout world, people, organisations and professions are struggling to find their place. In this, occupational therapy is no exception (Jenkins, 1993). Various pressures associated with political and economic reform are impacting on all facets of occupational therapy, including the provision of direct services to clients (Ostrow & Joe, 1983), funding for research to test and refine our knowledge base (Dawkins, 1987; Yerxa, 1983) and the position of occupational therapy education within institutions of higher learning (Dawkins, 1987). These pressures challenge occupational therapy educators to define 1) what occupational therapy is; 2) what occupational therapy education programs are; 3) why our educational programs look the way they do; and 4) what outcomes we expect from educational programs. How do we answer these questions?

Historically, occupational therapy educational programs have evolved out of an apprenticeship-training model (Anderson & Bell, 1988; Coleman, 1992a,b,c; Hopkins, 1988) which is characteristic of most medical programs. This apprenticeship model influenced occupational therapy curriculum designers to construct programs which prepare students to work in broad areas of practice (physical disabilities, psychiatry, paediatrics), or with specific ‘diagnostic’ groups (‘CVA’, acute anxiety disorders, dementia, learning disabilities), or in different contexts (acute care, community, schools). However, the scope of occupational therapy practice has undergone continual expansion since its inception (Reed, 1993; Yerxa, 1992) and new contexts for practice and classifications of diseases and disorders make it impossible for occupational therapy curricula to address all possibilities. What should we include?

More recently, pressures from colleges and universities challenge occupational therapy educators to make educational programs more ‘academic’ (Yerxa & Sharrott, 1986), that is, more theoretical and research oriented with less emphasis on practical skills and labour intensive modes of ‘teaching’. Course contact hours are being reduced, tutorial structures are under threat and large lectures or ‘independent learning’ modes encouraged. This places even more pressure on curriculum developers to make decisions about what objectives can be achieved and what ‘content’ should be included. How do we decide?

The profession demands our programs be theoretically sound yet retain their capacity to prepare students with the ‘tools’ for practice and research in a culturally diverse world. The profession also expects that educational programs instil in students a sense of professional identity in order to ‘counter’ groups who suggest they can provide ‘occupational therapy’. How do we accomplish this?

PURPOSE:

This focus of this paper is on describing how one occupational therapy program (The University of Sydney, Australia) has attempted to answer these questions. An undergraduate occupational therapy program has rejected the legacy of the ‘apprenticeship’ era in occupational therapy education and designed a course structure to be congruent with a model of occupational therapy, an evolving Australian version of ‘Occupational Performance’ (Chapparo & Ranka, 1992). Although other programs have moved in similar directions using different models (Dalhousie University, University of South Australia; Thomas Jefferson University), what appears unique about this program is its application of occupational performance principles to the education of students; that is, we address the ‘occupational need’ of students and prepare them for the ‘occupational role’ of occupational therapists. This represents an initial step in the development of a theoretical rationale for the preparation of occupational therapists which has been created from a model of occupational therapy practice rather than models of education.

A description of the altered course structure and a discussion of how the application of occupational performance constructs to the preparation of occupational therapy students for the role of ‘occupational therapist’ follows:

BACKGROUND:

The four year Bachelor of Applied Science course in occupational therapy at The University of Sydney graduates up to 150 students annually. We also have a comprehensive graduate program with coursework and research options. Our curriculum evolved from an undergraduate program based on a medical model of diagnosis and disease to one founded on the philosophy, assumptions and principles of occupational therapy as reflected in the model of occupational performance (Chapparo & Ranka, 1992). The transition to this new structure has been an evolutionary process which commenced in 1984 as a result of curriculum review (School of Occupational Therapy, 1986). Through a process of ongoing review and formal curriculum evaluation conducted in 1991, the initial model of occupational performance as well as its use as a theoretical foundation for occupational therapy education was refined to the point presented here.

MODEL OF OCCUPATIONAL PERFORMANCE:

The conceptual framework used to design the course is an Australian version of Occupational Performance (Chapparo & Ranka, 1992) currently being developed. This model of Occupational Performance builds on and extends similar developments in the United States (American Occupational Therapy Association, Inc., 1973) and Canada (Canadian Occupational Therapy Association, 1991).

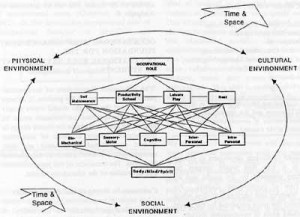

The Australian version is represented by an interactive structure of eight primary constructs, including: occupational performance, occupational role, occupational area, components of performance, core elements, environment, space and time (Fig.1). The interaction within and between these constructs explains the nature of occupational therapy and occupational therapy’s view of people and the world. Occupational performance identifies the domain of concern of occupational therapy as being the performance of human occupations. We acknowledge that humans have an occupational existence and aim to address their occupational need (Chapparo & Ranka, 1992)

Figure 1: A model of Occupational Performance (Adapted from Chapparo & Ranka, 1992).

This model maintains that a person’s engagement in human occupations is organised by the occupational roles they assume either by choice or out of need and expectation. Occupational roles may have a social dimension but are primarily configurations of activity from one or all of the major occupational areas. The nature of occupational therapy practice is shaped by first identifying the occupational roles clients possess, desire, require and are within their capacity. The primary goal of therapy is for those who receive occupational therapy services to be able to identify, choose and perform needed or desired occupational roles within their capacity to the satisfaction of themselves or significant others (Ranka & Chapparo, 1993).

OCCUPATIONAL PERFORMANCE AS A FOUNDATION FOR CURRICULUM STRUCTURE

The application of this model to curriculum structure resulted in a re-configuration of subject content away from diagnosis and disease to a structure based on occupational performance constructs. First, subjects were re-organised and re-named as indicated below (Table 1).

| Previous Subject Structure: |

Occupational Therapy

Sensory Motor Processes

Psychosocial Processes

Lifestyle & Lifespan Development

Interdisciplinary Studies

Selected Studies

Special Investigation

Clinical Education

Biological Sciences

Behavioural Sciences

| Current Subject Structure: |

Occupational Therapy Theory & Process

Occupational Role Development

Human Occupations

Components of Occupational Performance

Evaluation of Occupational Therapy Programs

Occupational Therapy Fieldwork

Biological Sciences

Behavioural Sciences

Table 1: Comparison between subjects in the 1980 BAppSc(OT) course and the current course (Note: each subject consists of several units which cross multiple years of the course.).

This required curriculum developers to arrange content in a way that would support the relationships proposed by the model and it’s generic view of occupational therapy. For example, teaching and learning activities which occur support the links purported by the model and the stated goals of occupational therapy.

Case study assignments require students to integrate subject content from several subjects to construct a total picture of a client in order to determine the focus of occupational therapy. For example, one case assignment may require students to consider issues associated with ‘occupational role development’, ‘human occupations’ and ‘components of occupational performance’ in designing specific intervention whereas, another case study may address theoretical issues (Occupational Therapy Theory and Process) associated with tests of cognition or personality inventories (Components of Occupational Performance) and their significance to client function (Human Occupations).

Application of theory to practice is always congruent with the view of occupational therapy described in the Model (Chapparo & Ranka, 1992). In this way students learn a process of thinking about occupational therapy and to synthesise knowledge, skills, attitudes and values from several areas of the course. This does create some difficulties, especially, when we are asked to demonstrate where students learn about, ‘occupational therapy in stroke rehabilitation’ or ‘occupational therapy in adolescent psychiatry’–the whole course prepares them for practice in these areas.

Additional information concerning structural aspects of the course will not be described in this paper.

OCCUPATIONAL PERFORMANCE AS A FOUNDATION FOR THE OCCUPATIONAL ROLE DEVELOPMENT OF STUDENTS

With subsequent development of occupational performance as a model for practice, it became apparent that the way the model views people and their occupational performance could be used as the theoretical basis for course design in occupational therapy in terms of supporting student occupational performance and their occupational role development as occupational therapists. The remainder of this paper describes this dimension of the educational model.

Construct 1: Occupational Performance

Occupational performance is the ability to perceive, desire, recall, plan and perform activities and tasks for the purpose of self-maintenance, productivity or school, play or leisure and rest to the satisfaction of one’s self, significant others or society (Chapparo & Ranka, 1992). An occupational need exists when occupational performance is compromised (Ranka & Chapparo, 1993). Educational practice is aimed at addressing the occupational needs of students and the profession through enhancing students occupational performance.

Occupational performance results from interactions that occur within and between two environments: an internal environment and an external environment. The internal environment consists of those aspects of performance which occur within a person. The external environment considers the broader context in which occupations are performed. The need for occupational performance can arise from the internal environment (a personal or collective goal) or the external environment (a need for shelter, financial security). Each of these environments influence each other Chapparo, & Ranka, 1992). The internal and the external environment are considered relative to the preparation of students.

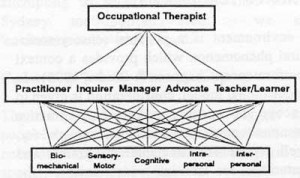

Construct 2: Occupational Roles

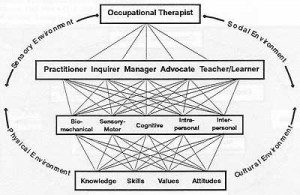

Occupational roles are patterns of occupational behaviour which consist of configurations of occupational activities and tasks from a number of occupational areas (Chapparo & Ranka, 1992). In this model, the occupational role of ‘occupational therapist’ is identified and represents the central focus of the model (Fig 2).

Figure 2: Occupational Role of ‘Occupational Therapist’

We assume that students have chosen the ‘occupational role’ of occupational therapist and our curriculum attempts to engage them in developing this role. We expect that at the end of our course students will be able to identify, choose and perform in the ‘role’ of occupational therapist to the degree expected of someone at entry level, and to the satisfaction of themselves, their clients, their employers and the profession.

In reality, not all students have made this choice on commencement of the course. This mirrors occupational therapy practice–often a major task of therapists is assisting clients in making decisions about needed or desired roles. Similar processes are put in place for new students to assist them in making role choices (occupational therapy versus another profession) and role transitions (eg., from high school student to university student, from daughter/son living at home to flatmate). This includes using the model to clarify what an occupational therapist is, describing what is required of someone commencing the development of this role (what the course is like) and what commencement of this role will not do (assure entry into a physiotherapy course). For example, Year Coordinators and ‘mentors’ assist in providing role transition support through regular group representative meetings, social events and facilitation of ‘peer networks’.

The assumption that students are commencing development of the occupational role of ‘occupational therapist’ suggests they should be viewed as new members of the profession. The label of ‘student’ is discarded and notions of students as ‘colleagues’ or ‘participants’ adopted. This change in our personal view of students prompts an attitude shift which is fundamental to this educational model. It immediately acknowledges that as ‘colleagues’, students are also ‘peers’. Educational practices used become more collaborative, adult-like and ‘mentor’ oriented, rather that purely directive and pedagogical. This shift is analogous to similar trends in the profession concerning the use of the word, ‘patient’ and an emphasis on ‘client-centred’ practice (Townsend, Brintnell & Staisey, 1991).

We anticipate that this view will also address some problems associated with role transition from student to therapist. For example, historically, graduation has marked the point of role change from student to therapist and the associated entry into the profession. This model acknowledges that ‘graduation’ is an important career stage in that a ‘license’ to practice is one step closer but graduation is not a demarcation point for entry into the profession: students are already colleagues.

Elimination of this demarcation point between student and therapist also means that the barrier between therapist and student is eliminated. This reinforces a desired aim of the curriculum, and the profession: that occupational therapists will engage in learning as a lifelong aim and participate in continuing professional education courses or re-enrol in higher degrees.

Construct 3: Occupational Areas

Occupational role performance requires that occupational therapists are able to perform a range of activities and tasks which arise from major occupational areas outlined in the model of Occupational Performance (Fig. 1) (Chapparo & Ranka, 1992). At a broad level, this educational model acknowledges that self-maintenance, leisure/play, and rest are important dimensions of occupational role development; however, the primary occupational area being developed by the curriculum is that of productivity and school occupations. Five ‘productivity/school’ categories of activities and tasks are identified: practitioner, teacher/learner, advocate, inquirer and manager (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Occupational Performance Areas

| Practitioner Area: The activities and tasks performed by practitioners relate to the skilful and safe application of the ‘tools’ of the profession in providing direct service to individuals, groups, organisations or communities. A major part of the curriculum focuses on developing the ability to provide direct intervention as well as accessing information about these ‘tools’. |

| Teacher/Learner Area: The activities and tasks performed by teachers and learners focus on assimilation, interpretation and synthesis of information, as well as, guiding, facilitating and instructing others or professing the fundamental tenets of occupational therapy. These skills are a major part of service provision. Participants learn how to teach clients, families, community groups, occupational therapy ‘teachers’ and each other. Consideration is given to individual learning styles in the design of teaching and learning methods. |

| Inquirer Area: The activities and tasks performed by occupational therapy inquirers involve questioning, examining, exploring, investigating, probing and researching. The essence of service provision hinges on knowing what questions to ask, how to ask them, where to find answers, how to interpret results, as well as, to construct programs and future plans based on findings. The process of designing occupational therapy programs requires inquiry skills as does the ability to evaluate programs and conduct research. Activities and tasks which require participants to function as ‘inquirers’ are embedded throughout the course. |

| Advocate Area: The activities and tasks associated with being an advocate require occupational therapists to assert, uphold, advance, promote and market. Increasingly, a professional need exists for occupational therapists to perform these activities and tasks. Occupational therapists are advocates for individual clients, groups and organisations and health issues, as well as, for themselves, their own programs and the profession. The curriculum includes several examples of ‘advocacy’ activities and tasks required by the occupational role of ‘occupational therapist’ |

| Manager Area: A final occupational area addressed by the curriculum is that of manager. The activities and tasks performed by managers involve administering, directing, supervising, coordinating and documenting relative to programs, employees, clients and organisations. Managerial activities can range from managing client therapy groups to organisations, supervising one student to large numbers of staff; documenting client progress to documenting a need for health services. The curriculum includes entry level managerial activities and tasks and demonstrates their application to more complex management situations. |

This categorisation is used to help make decisions concerning what activities and tasks to include and what teaching/learning methods will be used. It ensures that consideration is given to the occupational areas which contribute to the role of an occupational therapist, and that the level of performance expectations are identified for each area (eg. level of managerial skill expected of a new graduate vs level of practitioner skill expected of a graduate certificate student; or level of inquiry skill expected of a new graduate vs level of inquiry skill expected of a doctoral candidate). It also contains structured experiences which facilitate student recognition of how activities and tasks which address one occupational area can be translated into other occupational areas. This occurs through self-classification ‘exercises’ in which students determine the occupational areas being addressed by various curriculum activities and tasks.

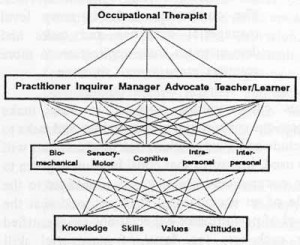

Construct 3: Components of Performance

The activities and tasks performed by occupational therapists in each of the occupational areas require blends of human component abilities. The curriculum attempts to develop participant component abilities to support activity and task performance in biomechanical, sensory motor, cognitive, intrapersonal and interpersonal areas (Fig.4).

Figure 4: Components of Performance

| Biomechanical Component: refers to the components of activities and tasks which involve the use of one’s body. For example, the physical ability to lift and handle objects or clients, as well as, the use of body postures to convey an image. |

| Sensory-Motor Component: refers to the components of activities and tasks which involve interpreting and acting on sensory information. For example, noticing that a line of questioning being used is causing client distress, or ‘feeling’ when to cease applying passive range of motion. |

| Cognitive Component: refers to the components of activities and tasks which involve the application of theory, constructing interpretations from data, creating new designs and plans, reasoning courses of action. For example, designing a piece of adapted equipment for a specific client problem, comparing conceptual models of practice, describing rationales for intervention. |

| Intrapersonal Component: refers to the components of activities and tasks which involve exploring and appreciating the impact of personal attitudes and values on one’s occupational role performance. For example, discussing ethical dilemmas, exploring personal reactions the impact of disability on peoples lives, developing confidence in one’s ability to stand up in front of an audience. |

| Interpersonal Component: refers to the components of activities and tasks which involve relating to and communicating with others. For example, using non-verbal communication skills, identification of empathic responses, discussing the views of other people in a group. |

This aspect of the model encourages educators to consider the scope of human component function that is required during occupational activity and task performance. For example, consideration is given to interpersonal (interpersonal component) factors involved during the application of physical handling techniques (biomechanical component), or the ability to read sensory cues arising from one’s own body (sensory-motor component) during public speaking exercises and apply visualisation techniques (intrapersonal component) to relax; or appropriate use of questioning (interpersonal component) to identify (cognitive component) client occupational role needs.

It also encourages educators to consider that the component contributions to performance will change according to the occupational areas being addressed. For example, the activities and tasks of a practitioner require a different blend of component function to those of a manager. The component emphasis placed on an activity or task is determined by the area being addressed and the level of occupational role performance being developed (eg. ‘novice’, ‘skilled’). This aspect of the curriculum demonstrates a need for a range of teaching and learning strategies including small group tutorials.

Construct 4: Core Elements

The fundamental element of occupational performance is the ‘body-mind-spirit’ unit. In this model, core elements are the course objectives which express knowledge, skills, attitudes and values to be gained (Fig. 5).

Course objectives are stated to reflect the aim of developing the occupational role of students, and objectives for each educational activity or task presented are congruent with this aim. The balance of knowledge, skills, attitudes or values to be addressed in any one task vary according to the area being addressed and the emphasis placed on component function during that particular task. For example, one ‘practitioner/advocate’ task may address ‘skill’ development in ‘interpersonal’ interactions, whereas another task may focus on an exploration of ‘attitudes’ and ‘values’ concerning the use of upper limb orthotic systems (biomechanical component). The model provides a guide to ensure that objectives are comprehensive in terms of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values and that they are focused on occupational performance.

Figure 5: Core elements

The model also encourages educators to consider that all participants in the course bring with them a range of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values which have been created by their own unique life experiences and personal endowment. This ‘prior learning’ contributes to shaping each participant’s component abilities. For example, some participants will excel at learning to use their body (biomechanical skill emphasis) while others will excel at creating new ideas (cognitive knowledge emphasis) or relating to others (intrapersonal skill emphasis). This pattern is reflected throughout other levels of the model; for example, prior learning may influence one participant to enjoy ‘managerial’ activities and tasks while others may prefer ‘inquirer’ activities and tasks. Educational practice in this model thrives on this diversity. It acknowledges that all participants are resources in the process of occupational role development and attempts to utilise the unique contribution of each one.

Construct 5: Environment

The environment is a physical-sensory-socio-cultural phenomenon which provides a context for performance (Chapparo & Ranka, 1992). In this educational model, consideration is given to the scope of occupational therapy practice environments participants are being prepared for, as well as, the environmental constraints and opportunities for learning which exist on the immediate campus and in the community (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: External Environment

Curriculum activities and tasks require students to explore sociocultural implications for practice including such things as factors affectingintercultural interaction, as well as what a ‘practice’ environment might consist of. Alternately, environmental factors place constraints on the type of educational experiences which can be provided and are considered in curriculum planning. For example, this curriculum has 550+ enrolled students in the BAppSc(OT) course for the four-year duration of the program–the constraints and opportunities abound. Curriculum practice must consider that there are ten first year tutorial groups and, very soon, four Schools of Occupational Therapy attempting to secure fieldwork sites in the Sydney metropolitan area: we are ‘environmentally’ challenged.

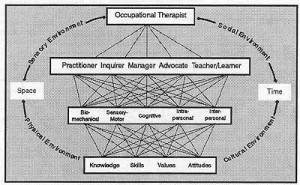

Constructs 7 & 8: Time and Space

The notions of time and space suggest that people have a past and a future and that occupational performance has both temporal and spatial dimensions (Fig. 7). These two constructs encourage educators to consider the ‘timing’ and ‘spatial’ complexity of curriculum activities and tasks. They reinforce a developmental approach to the design of curriculum activities and tasks and remind educators that participants may not perceive themselves as ‘ready’ (time) for the complexity of tasks (space) they are expected to participate in. This dimension to the model ensures that opportunities for choice exist in the curriculum, including choice in goals, choice in style of participation and choice in assessment methods. These constructs also ensure that consideration is given to the amount of time participants spend on various activities and tasks.

The complete educational model

The use of the complete model (Appendix 1) allows an evaluation of the total curriculum in terms of how well it prepares students for what will be expected of them. It can be used to map the curriculum in terms of content focus and level of competence addressed relative to the occupational areas of concern to occupational therapists at an undergraduate and graduate level.

Using this foundation, occupational therapy educators can make choices from a range of educational models and approaches (for example, problem-based learning, self-directed learning, experiential learning, lifelong learning, didactic instruction, computer-aided instruction) but are able to apply them within the context of a common view of occupational therapy. Finally, it provides an educational and professional rationale for curriculum choices made concerning what and how we teach.

Figure 7: Time and Space

SUMMARY

A model for the professional preparation of occupational therapists has been described in this paper. This model represents an attempt to uncouple educational programs from their original medical foundation in favour of an occupational therapy one. Through the use of occupational performance as an educational model for the professional preparation of occupational therapists, students learn about occupational therapy in a manner which is congruent with our professional philosophy, values and assumptions. This marks the emergence of an educational theory on which decisions can be made about occupational therapy curricula which is unique to our profession. From this perspective, graduates gain not only a theoretical understanding of occupational therapy, they are prepared for the occupational activities and tasks required of an occupational therapist now and in the future, that is, the activities and tasks of practitioners, inquirers, teachers/learners, inquirers, advocates and managers.This ensures their employability.

REFERENCES:

American Occupational Therapy Association, Inc. (1973). The roles and functions of occupational therapy personnel. Rockville, MD: Author

Anderson, B., & Bell, J. (1988). Occupational therapy: Its place in Australia’s history. NSWAOT: Sydney.

Canadian Occupational Therapy Association (1991). Guidelines for client-centered practice in occupational therapy. (Available from CAOT, 110 Eglinton Ave., West, 3rd floor, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4R 1A3).

Chapparo, C., & Ranka, J. (1992). Occupational performance model (draft manuscript). (Available from authors, School of Occupational Therapy, The University of Sydney, PO Box 170, Lidcombe, NSW Australia, 2141)

Coleman, W. (1992a). Maintaining autonomy: the struggle between occupational therapy and physical medicine. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 46(1), 63-71.

Coleman, W. (1992b). Looking back–Evolving educational practices in occupational therapy: the War Emergency Courses, 1936-1954, 44(11), 1028-1036.

Coleman, W. (1992c). Looking back–the curriculum directors: influencing occupational theapy education, 1948-1964, 44(3), 244-246.

Dawkins, J.S. (1987). Higher education: a policy discussion paper. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

Hopkins, H.L. (1988). An historical perspective on occupational therapy. In H.L. Hopkins and H.D. Smith (Eds), Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy (7th ed.) (pp. 16-37). Philadelphia: JB Lippincott

Jenkins, M. (1993). So we think we are unique…. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 56(1), 1

Ostrow, P., & Joe, B.E. (1983). Negotiating the environment: Ahieving quality care in a time of flux. American Journal of Occupaitonal Therapy, 36(12), 779-781

Ranka, J., & Chapparo, C. (1993, September). Occupational performance: A practice model for occupational therapy. Paper presented at the 6th State Conference of OT Australia AAOT-NSW, Mudgee, NSW.

Reed, K.R. (1993). the beginnings of occupational therapy. In H.L. Hopkins, & H.D. Smith (Eds.) Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy (8th ed.) (pp. 26-43). Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott

School of Occupational Therapy (1986). Stage IV review, Bachelor of Applied Science (Occupational Therapy) course. (Available from authors, School of Occupational Therapy, The University of Sydney, PO Box 170, Lidcombe, NSW Australia, 2141)

Townsend, E., Brintnell, S., & Staisey, N. (1991). Developing guidelines for client-centered occupational therapy practice. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 57(2), 69-76.

Yerxa, E. R. (1983). Research priorities. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 37(10), 699.

Yerxa, E.R. (1992). Some implications of occupational therapy’s history for its epistemology, values and relation to medicine. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 46(1), 79-83.

Yerxa, E.R., & Sharott, G. (1986). Liberal arts: the foundation for occupational therapy education. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 40(3), 153-159.